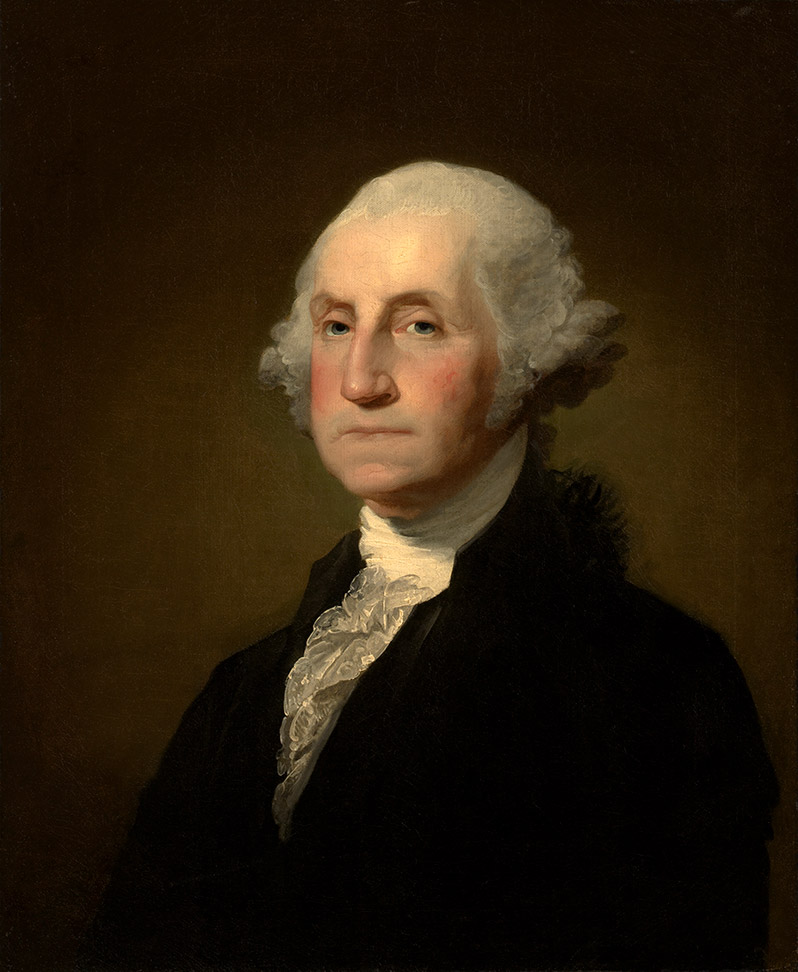

Elizabeth Fenn, author of Pox Americana, notes that artists tend to flatter their subjects. This is certainly true of the portraits we are familiar with of George Washington, our first President and the hero of the American Revolution. The reality that is overlooked in these portraits are the scars George Washington had from a bout of smallpox he survived as a young man of 19. In 1751, he set out with his half-brother, Lawrence, to the island of Barbados in the hopes that Lawrence’s consumption (tuberculosis) would improve in more favorable conditions. Unfortunately, this did not work and Lawrence would die of his malady the following July in 1752.

During his visit to Barbados, George contracted smallpox and was bedridden for a month combatting the high fevers, sores, rashes, and body aches that come with the dreaded virus whose technical name is Variola. This episode in young George Washington’s life would have a profound impact on history. It made Washington immune to the disease that would later devastate the North American Continent. In July of 1775, just three months into the conflict with England that would become known as the American Revolution, George Washington took command of the patriot army. He faced not only the greatest military power in the world, but also the scourge of Variola. He had a difficult decision to make: Should he inoculate the army?

George Washington was a firm believer in smallpox inoculation, perhaps because of his history with the disease. But unlike many vaccines today, early forms of inoculation would give people a less severe form of the disease in order to create immunity. Even a minor bout with smallpox could leave a person incapacitated and Washington could not afford to have a large portion of his under-trained and inexperienced soldiers out of commission for any significant period of time.

Washington decided the best course of action was to have new soldiers inoculated upon recruitment. This decision was met with controversy and concern. Though it could (and did) save the bulk of his army, there was a 1% mortality rate due to the primitive form of inoculation used at the time. Furthermore, inoculation was not yet accepted by society and Washington faced a great deal of criticism for introducing it to the patriot army. The idea of intentionally giving someone a mild version of a disease seemed immoral to many colonists. Failing to require inoculation would have clearly had more devastating results, negatively impacting the fight for American Independence.

Despite the preventative measures he implemented, smallpox continued to plague Washington’s efforts. Canada might have become the 14th Colony had it not been for a Variola outbreak. Of the 1,900 soldiers involved in the siege of Quebec in December 1775, approximately 900 had contracted smallpox. Their replacements had even higher numbers of infected soldiers. Of the 10,000 soldiers that were to be part of the invasion of Canada, 3,000 came down with smallpox.1 Warfare created the perfect conditions for a disease like smallpox to flourish. Close contact with a large number of people, poor hygiene, and unclean living conditions allowed the disease to spread like wildfire. George Washington ordered the immediate quarantine of anyone showing signs of the illness but, by that time, the disease has already spread.

The British were typically immune to smallpox, like Washington. England had far more outbreaks of Variola in the 18th century than did North America. While they had fewer cases, it is suspected that the British used a kind of biological warfare against Washington’s troops by sending infected British soldiers to the American lines in order to spread the disease amongst patriot forces.

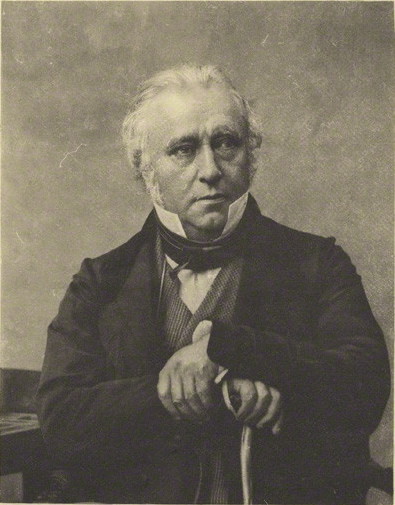

The Nineteenth Century British Politician and Historian, Thomas Babington Macaulay, compares the Variola virus to the plagues that ravaged Europe in earlier centuries; “That disease . . . was then the most terrible of all the ministers of death. The havoc of the Plague had been far more rapid; but the Plague had visited … once or twice and the smallpox was always present, … tormenting with constant fears all whom it had not yet stricken, leaving on those whose lives it spared the hideous traces of its power.”2 Though the notion of contagion was not yet fully accepted within the late 18th century medical community, the average person understood that smallpox was able to be transmitted through bodily contact and even through objects that had been touched by those suffering the illness.

Unfortunately, warfare made quarantining difficult and had an enormous impact on Washington’s military strategy and the war for American Independence. Though it is difficult to determine the number of deaths caused by disease, John Adams suggested in a letter to his wife Abigail; that, “Disease has destroyed Ten Men for Us, where the Sword of the Enemy has killed one.”3 Had it not been for George Washington’s strict orders regarding containment, inoculations, and limited access of outsiders to military camps, the Variola outbreak would have had far more devastating effects. Would Washington have had this keen sense had it not been for his own experience with smallpox in Barbados? Could smallpox have caused the loss of the American Revolution and continued rule by England? Americans can be glad that we will never have to know.

“Washington Crossing the Delaware,” Oil Painting by Emanuel Leutze, 1851.

INTERESTING FACTS

Portrait of George Washington (1732 – 99) by Gilbert Stuart, completed in 1796.

Smallpox: (Noun) An acute contagious febrile disease of humans that is caused by a poxvirus (species Variola virus of the genus Orthopoxvirus), is characterized by a skin eruption with pustules, sloughing, and scar formation, and is believed to have been eradicated globally by widespread vaccination. (Merriam-Webster Dictionary)

Portrait of Lawrence Washington, older half-brother of George Washington, possibly by painter Gustavus Hesselius, circa 1738.

Inoculation: (Noun) The introduction of a pathogen or antigen into a living organism to stimulate the production of antibodies. (Merriam-Webster Dictionary)

The Siege of Quebec (December 31, 1775) was an unsuccessful American attack on the British stronghold. In the winter of 1775–76, American Revolutionary leaders detached some of their forces from the Siege of Boston to mount an expedition through Maine with the aim of capturing Quebec. On December 31, 1775, under General Richard Montgomery and Colonel Benedict Arnold, an inadequate force of roughly 1,675 Americans assaulted the fortified city, only to meet with complete defeat. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Quarantine: (Noun) A state, period, or place of isolation in which people or animals that have arrived from elsewhere or been exposed to infectious or contagious disease are placed. (Oxford Dictionary)

Photograph of the British Historian and Whig Politician Thomas Babington Macaulay by French Photographer Antoine Claudet, 1860s.

Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800 – 1859) was an English Whig politician, essayist, poet, and historian best known for his History of England, 5 vol. (1849–61); this work, which covers the period 1688–1702, secured his place as one of the founders of what has been called the Whig interpretation of history. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Enjoy this article? Please consider supporting St. Luke’s with a donation!

Works Cited

1) Pomeroy, Ross, “How George Washington Used Vaccines to Help Win the Revolutionary War,” 25 September 2016: https://www.realclearscience.com/blog/2016/09/how_vaccination_helped_win_the_revolutionary_war.html

2) Becker, Ann M., Smallpox in Washington’s Army: Strategic Implications of the Disease during the American Revolutionary War, The Journal of Military History, Vol. 68, No. 2 (Apr., 2004), pp. 381 – 430: https://www.sjsu.edu/people/ruma.chopra/courses/h174_MW_F11/s3/smallpox_GWarmy.pdf

3) Adams, John, “Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams,” 13 April 1777: http://www.masshist.org/digitaladams/archive/doc?id=L17770413jasecond&bc=%2Fdigitaladams%2Farchive%2Fbrowse%2Fletters_1774_1777.php

Works Referenced

Fenn, Elizabeth A., Pox Americana: The Great Smallpox Epidemic of 1775 – 82, 2002, Kindle Edition.

About the Author

John Ericson is the Outreach Coordinator and a Public Historian for St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum. John holds a degree in History from Roanoke College and a Masters of Divinity from the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg. In addition to John’s role at St. Luke’s, he is the Pastor of Reformation Lutheran Church in Newport News, Virginia. John is married to Oneita Jamerson Ericson, a native of Isle of Wight County, Virginia. They have three sons, Matthew, Thomas, and James, as well as two granddaughters, Carys and Lennon. The Ericsons currently reside in Hampton, Virginia. John has been teaching Reformation History and the Early American Religious Experience for more than thirty years.