One of the great innovations in rights from the American Revolution and founding was religious liberty as a natural right. Virginians James Madison and Thomas Jefferson have justifiably received a lion’s share of the credit for religious liberty. The typical story crediting Madison and Jefferson has much evidence to support the argument.

In 1776, the Virigina Convention adopted the Virginia Declaration of Rights drafted by George Mason. The document offered the liberal-minded Enlightenment idea of religious toleration. A young Madison, however, thought that mere toleration of dissenters was not enough and instead advanced the idea of freedom of conscience. “All men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience.”

Over the next decade, Jefferson and Madison struggled for religious liberty as a natural right. In 1785, Madison wrote his “Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments” arguing against a controversial bill for limited religious establishment proposed by Patrick Henry. Madison wrote, “The Religion then of every man must be left to the conviction and conscience of every man; and it is the right of every man to exercise it as these may dictate. This right is in its nature an unalienable right.”

The Virginia legislature then passed Jefferson’s Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom in early 1786. The new law stated, “We are free to declare, and do declare, that the rights hereby asserted are of the natural rights of mankind.” The resulting disestablishment of the official church in the state was a watershed moment for religious liberty.

Their dedication to religious liberty bore fruit in American constitutionalism. While Madison had opposed a bill of rights during the ratification debate, Jefferson helped to persuade his friend to support it to protect the essential rights of man. Representative Madison urged the First Congress to adopt the amendments and became their primary author. The First Amendment read, “Congress shall make no law…prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

As if to emphasize the point, Madison wrote a series of published essays in the early 1790s that included religious liberty. In his 1792 essay, “On Property,” he made the brilliant point that individuals not only have a right to property, but they have an inviolable property in their rights. He asserted that, “Conscience is the most sacred of all property.”

Jefferson and Madison made an undeniably significant contribution to religious liberty. However, this focus has hidden the unheralded—and profoundly significant—role played by George Washington in helping to create religious liberty. Washington’s contribution advancing religious liberty in a practical way as general, president, and statesman on the national level for decades has generally gone unrecognized in the popular imagination.

Congress appointed Washington Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army in June 1775. Washington sought to form a truly national army and continental outlook among the soldiers from different states and denominations to forge a common purpose. He had also had much work to do to instill discipline and virtue for ordered liberty among self-governing citizen-soldiers in the republican army.

Upon arriving in Boston, General Washington issued orders forbidding cursing, drunkenness, and skinny-dipping in front of ladies. He worked with Congress to allow chaplains to serve the spiritual needs of regiments and then brigades. They generally reflected the denominational allegiances of their men. Washington encouraged mutual respect and quickly banned prejudicial practices such as Pope’s Day in which Roman Catholic practices were mocked and the pope burned in effigy.

The General promoted religious observance that were consistent with religious liberty. Washington required soldiers to attend religious services under the guidance of their chaplains “to implore the blessings of heaven upon the means used for our safety and defense.” In Boston and throughout the war, he also directed them to join day of thanksgiving for liberty and harmony as well as days of fasting and prayer to seek common forgiveness for transgressions.

As statesman and president, Washington repeatedly acknowledged the role of divine providence in securing victory in the American Revolution and securing the blessings of civil and religious liberty in a free government. President Washington also received congratulatory messages from all denominations and responded to each.

Washington wrote letters to religious congregations including Presbyterians, Baptists, Quakers, Roman Catholics, and Jews among several others. His letters promulgated the same message to each denomination: the American regime supports religious liberty for all, and all should comport themselves as virtuous, moral citizens in a republic.

Washington adopted the common founding view of the role of religion in a republic. Religion was the basis for morality and virtue, and morality and virtue were the foundation of good citizenship. Therefore, religion had a role as an indispensable pillar of republican government. This logical syllogism was predicated upon the natural right of religious liberty.

Perhaps the most notable of Washington’s letters to the denominations was the one he wrote to the Hebrew Congregation in Newport, RI. He famously stated that, “All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship.” He continued, asserting religious liberty as an inalienable natural right.

“It is now no more that toleration is spoken of as if it were the indulgence of one class of people that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights, for, happily, the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.”

Considering the Anti-Semitism experienced by Jews at the time and that Jews were only tolerated at best in Europe with Enlightenment reforms, Washington’s statement demonstrates a remarkable liberality. Washington ends the letter on a poetic note borrowing from the Book of Micah:

“May the children of the stock of Abraham who dwell in this land continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other inhabitants—while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree and there shall be none to make him afraid.”

While President Jefferson’s later “Letter to the Danbury Baptists (1802) has acquired near-scriptural status in the Supreme Court as the basis for modern understanding of church-state relations, Washington’s lesser-known letters to the denominations were highly significant contributions to religious liberty in the early republic. They should gain at least an equal status in helping us to understand religious liberty and the American founding.

Washington’s coupling of religious liberty and religious duties in a republic were clearly articulated in his seminal Farewell Address. “Let us with caution indulge the supposition that morality can be maintained without religion…. ’Tis substantially true, that virtue or morality is a necessary spring of popular government.” The American founding offered the great contribution of religious liberty as a natural right to the world, but the survival of the republic required virtuous, self-governing citizenry.

Most people (and scholars) reflexively give Jefferson and Madison credit for the creation of religious liberty. They would be wise to consider that George Washington deserves a great deal more credit for establishing religious liberty than he typically receives.

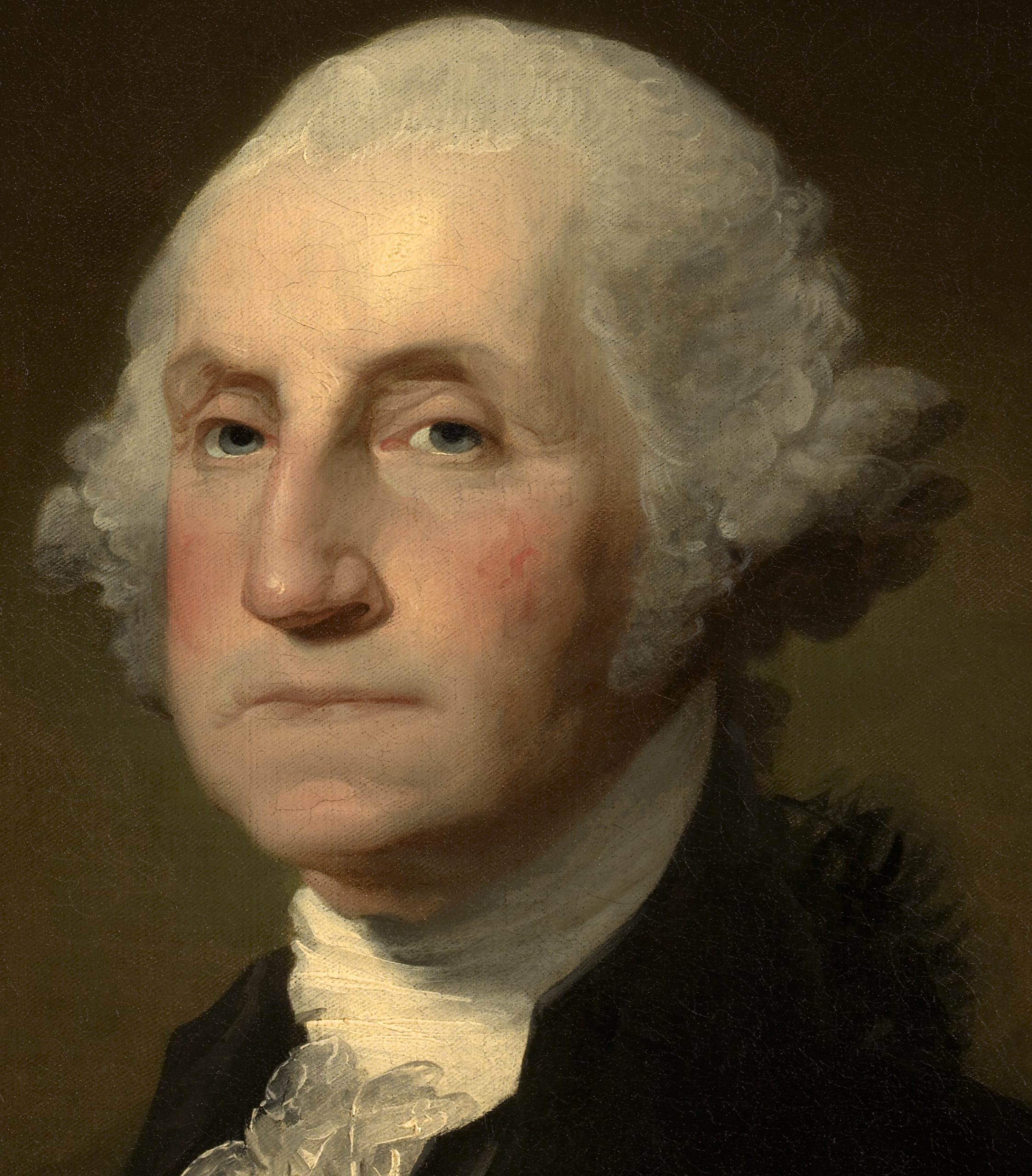

(Above) Portrait of James Madison, oil on canvas painting, 1816.

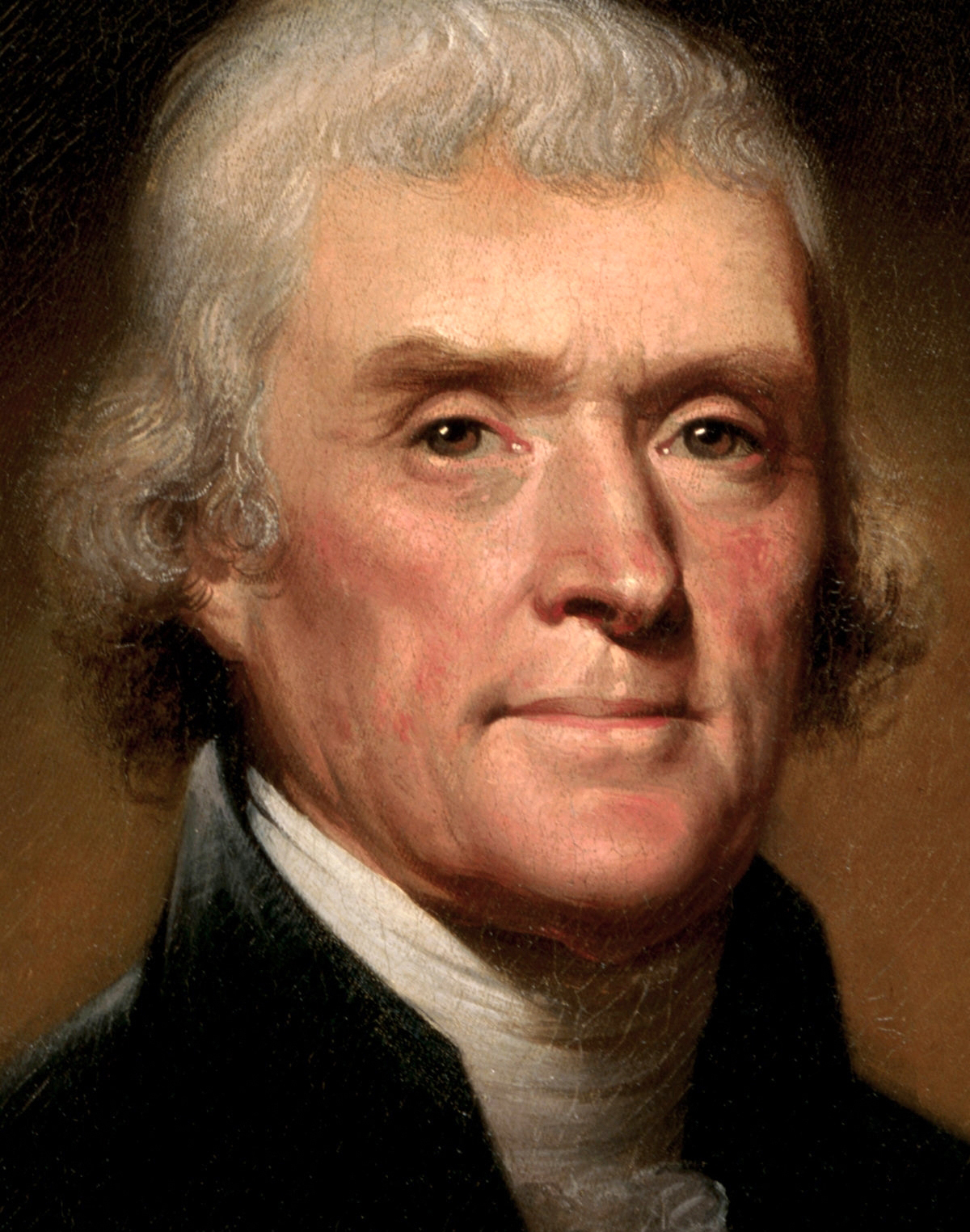

Portrait of Thomas Jefferson, oil on canvas painting by American painter Rembrandt Peale.

Portrait of George Mason, oil painting, by Dominic W. Boudet, copy of a ruined original by artist John Hesselius, 1750.

Portrait of Patrick Henry, oil on canvas painting by George Bagby Matthews after the original painting by Thomas Sully, circa 1891.

Portrait of George Washington, oil on canvas, by Gilbert Stuart, 1803.

Enjoy this article? Please consider supporting St. Luke’s with a donation!

About the Author

Tony Williams is a Senior Teaching Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute. He is the author of six books on the American founding including Pox and the Covenant and Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America. He is currently writing a book on the Declaration of Independence. Tony Williams has been a frequent lecturer at St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum.