On June 6, 1855, a steam ship known as the Ben Franklin came into port in Norfolk, Virginia for repairs. The ship had traveled from St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands, a place Yellow Fever was known to be prevalent. Local authorities were concerned about the possibility of Yellow Fever onboard because of the ship’s origins and interviewed Captain Byner upon arrival. Particularly concerning was the death of one of the crewmen during the voyage. Captain Byner misrepresented the death as having been from a heart attack, allowing the Ben Franklin to move on to Gosport unhindered and spreading one of the worst epidemics in Virginia’s history.

By July, Yellow Fever had begun to infect people throughout the region, spread by those who had boarded the Ben Franklin. By mid-summer, the casualty rate was roughly 80 people per day and as much as half of the populations of Norfolk and Portsmouth began to flee their homes. Refugees were soon being refused at bayonet point by surrounding cities who feared the spread of the contagion. Businesses were closed, church services suspended, and the remaining citizens lived in terror of contracting the deadly disease.

Hotels in Norfolk were being used as hospitals to care for those infected. Relief funds were set up to care for those orphaned and to pay medical expenses for those suffering from the disease. Medical personnel came in from other areas to lend aid to the afflicted cities.

This was not the first time Yellow Fever had ravaged Norfolk and Portsmouth. Early outbreaks in 1795, 1802, 1821 and 1826 had their effects, but nothing like the devastation of the Summer of 1855. By the end of that summer, most of the remaining citizens in the affected areas had been infected and some 3,000 people had died from Yellow Fever.

All of the conditions were ripe for such an outbreak. The Summer of 1855 was hotter and more humid than the years just before and after, and higher rainfall encouraged the mosquito population.1 Yellow Fever has an insect vector, meaning that mosquitos are able to carry and transmit the horrible virus. Unfortunately, the role mosquitos played in spreading Yellow Fever was unknown at the time. The poorer areas were most impacted because of crowded living conditions and the lack of sanitation.

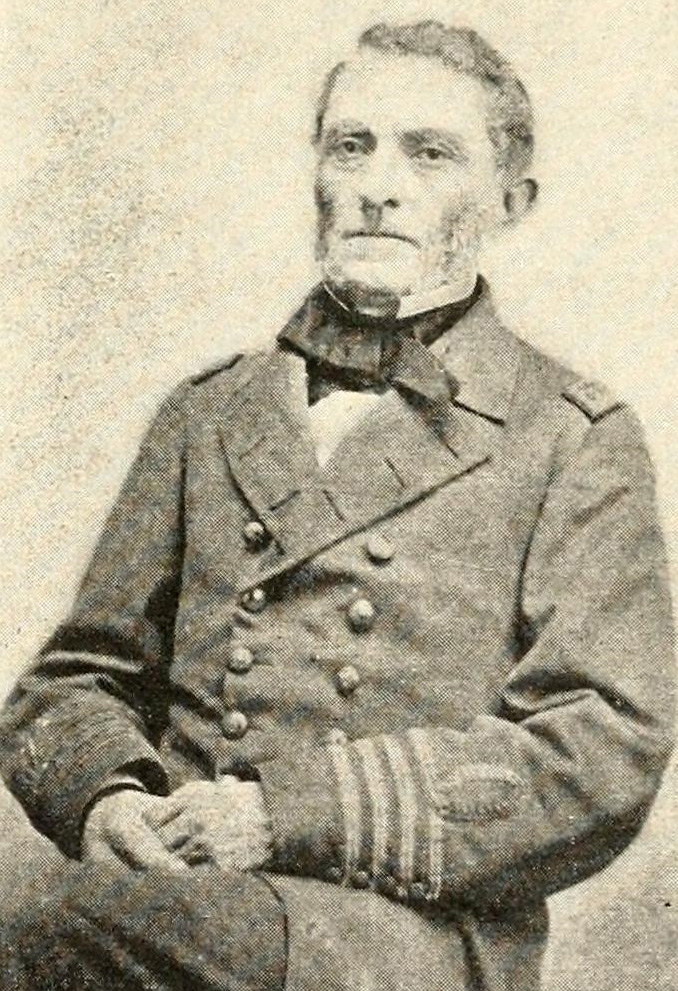

Panic was another catalyst for the spread of the disease. Frantic citizens fled only to spread the disease to the places where they sought refuge. In a letter to Captain Samuel Barron of the Gosport Naval Yard, his friend, W. R. Palmer, could offer little solace; “I cannot write to offer you comfort or consolation. This can only come from your Almighty Creator, but your friends do indeed sympathize with you in your sad bereavement…May you be long spared to comfort and protect those who are left to you. I really do wish I could be of any use to you in any way.” 2

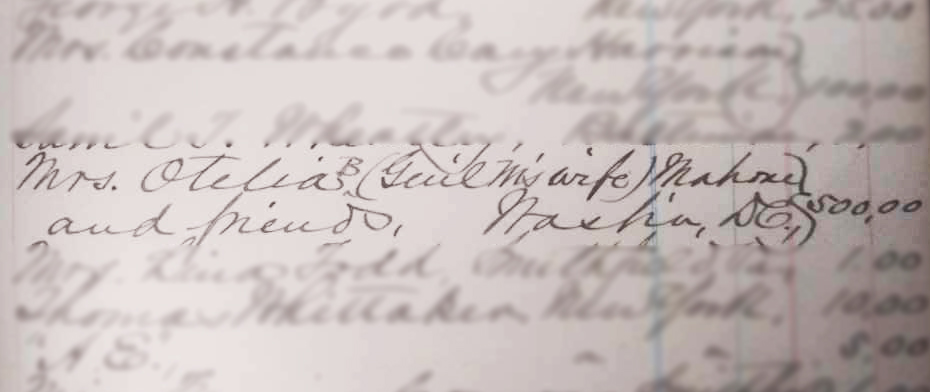

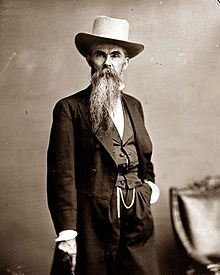

Among the casualties of Yellow Fever in that awful summer of 1855 was one Otelia Voinard Butler, the wife of Dr. Robert Butler of Smithfield, Virginia. Dr. Butler was the Adjutant General for Virginia during the War of 1812 and Virginia State Treasurer from 1846 until his death in 1853. Perhaps more notably, Otelia Butler was the mother-in-law of William Mahone, a railroad engineer and graduate of the Virginia Military Institute who would go on to become a Major General in the Confederate States of America and later dubbed “The Hero of the Crater.” Otelia Butler was residing with her daughter, also named Otelia, when the Yellow Fever outbreak occurred. She succumbed to the disease on August 21, 1855. William Mahone and Otelia Butler Mahone soon fled the city to join his mother in Jerusalem, Virginia, located in South Hampton County. Eventually, Otelia Voinard Butler was laid to rest aside her Husband at the “Old Brick Church” in Isle of Wight County, today known as St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum. Today, the graves of Dr. and Mrs. Butler lay beneath a well-worn and crumbling stone, barely legible, just east of the church building. Though William and Otelia Mahone were not buried at St. Luke’s, a ledger by Rev. David Barr from the 1885-1894 renovation of the church building notes a contribution from Otelia B. Mahone, wife of General Mahone and friends for $500 (a sum that would be worth over $14,000 based on today’s value of the dollar).

Ledger entry noting a $500 donation towards the renovation of the Old Brick Church by Mrs. Otelia B. Mahone and friends, circa 1885 – 1894.

The Yellow Fever Outbreak of 1855 was one of the worst episodes in Virginia’s history. Many similarities can be found between the responses to the 1855 Yellow Fever outbreak and our current circumstances. In times of critical risk to the health of our communities, we need to take reasoned steps to ensure the safety of our neighbors and families. One of the legacies of that terrible summer of 1855 is the generosity and courage of those who sought to care for those in need. We see and honor that same spirit, clearly evident in those caring for us all during the current pandemic. The staff of St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum thanks those who are on the front lines of the current battle against another deadly disease. We wish you all health and safety as we continue to weather this storm together but apart.

INTERESTING FACTS

Yellow Fever: (Noun) A tropical viral disease affecting the liver and kidneys, causing fever and jaundice and often fatal. It is transmitted by mosquitoes. (Oxford Dictionary)

Established as Gosport Shipyard in 1767, this shipyard has a long history that continues today in its present capacity as the Norfolk Naval Shipyard. The U.S. Federal Government purchased the shipyard from the Commonwealth of Virginia in 1801 and has expanded it dramatically from the original 16 acre tract that was once the Gosport Shipyard.

Photo of Captain Samuel Barron, who was stationed at the Gosport Naval Yard in 1855. At the beginning of the Civil War, Captain Barron resigned from the U.S. Navy and joined the Virginia Navy as Chief of the Office of Naval Detail and Equipment.

Photo of Otelia Butler Mahone, daughter of Otelia Voinard Butler, shown with an unknown child, possibly her daughter.

Photo of William Mahone, husband of Otelia Butler Mahone and son-in-law of Otelia Voinard Butler, both pictured above.

Enjoy this article? Please consider supporting St. Luke’s with a donation!

Works Cited

1) Hamilton, Lara Marie, Thesis: The Yellow Fever Epedimic of 1855 in Norfolk and Portsmouth: An Analysis of Social Response and Climate, April 2001: http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/yellow-fever/yfthesis.html

2) Palmer, W.R., Letter to Capt. Samuel Barron dated August 24, 1855, Letters to Capt. Samuel Barron, Gosport Navy Yard, August to October 1855, Papers of the Barron Family; Special Collection of the University of Virginia Library: https://www.sjsu.edu/people/ruma.chopra/courses/h174_MW_F11/s3/smallpox_GWarmy.pdfhttp://www.usgwarchives.net/va/yellow-fever/barronletters.html#barron

About the Author

John Ericson is the Outreach Coordinator and a Public Historian for St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum. John holds a degree in History from Roanoke College and a Masters of Divinity from the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg. In addition to John’s role at St. Luke’s, he is the Pastor of Reformation Lutheran Church in Newport News, Virginia. John is married to Oneita Jamerson Ericson, a native of Isle of Wight County, Virginia. They have three sons, Matthew, Thomas, and James, as well as two granddaughters, Carys and Lennon. The Ericsons currently reside in Hampton, Virginia. John has been teaching Reformation History and the Early American Religious Experience for more than thirty years.