Diseases like COVID-19 have always been a part of human history whether it has been bubonic plague, malaria, yellow fever, polio, influenza, typhoid, or AIDS. The greatest killer throughout history was the dreaded smallpox virus that was highly contagious and resulted in death rates typically between 15 and 30 percent and as high as 90 percent in the case of Native Americans.

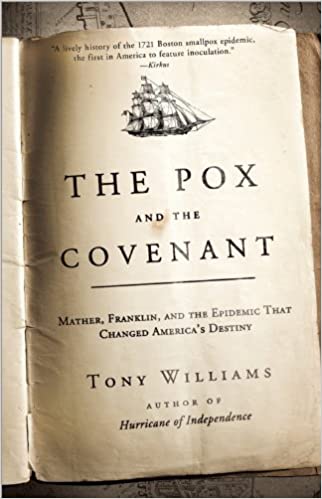

Several years back, I wrote a book about a 1721 Boston smallpox epidemic and the introduction of inoculation into colonial America entitled The Pox and the Covenant. The fact that there are parallels between that epidemic and our current pandemic should not surprise us given the immutable character of human nature. However, that fact should also give us comfort that we can endure.

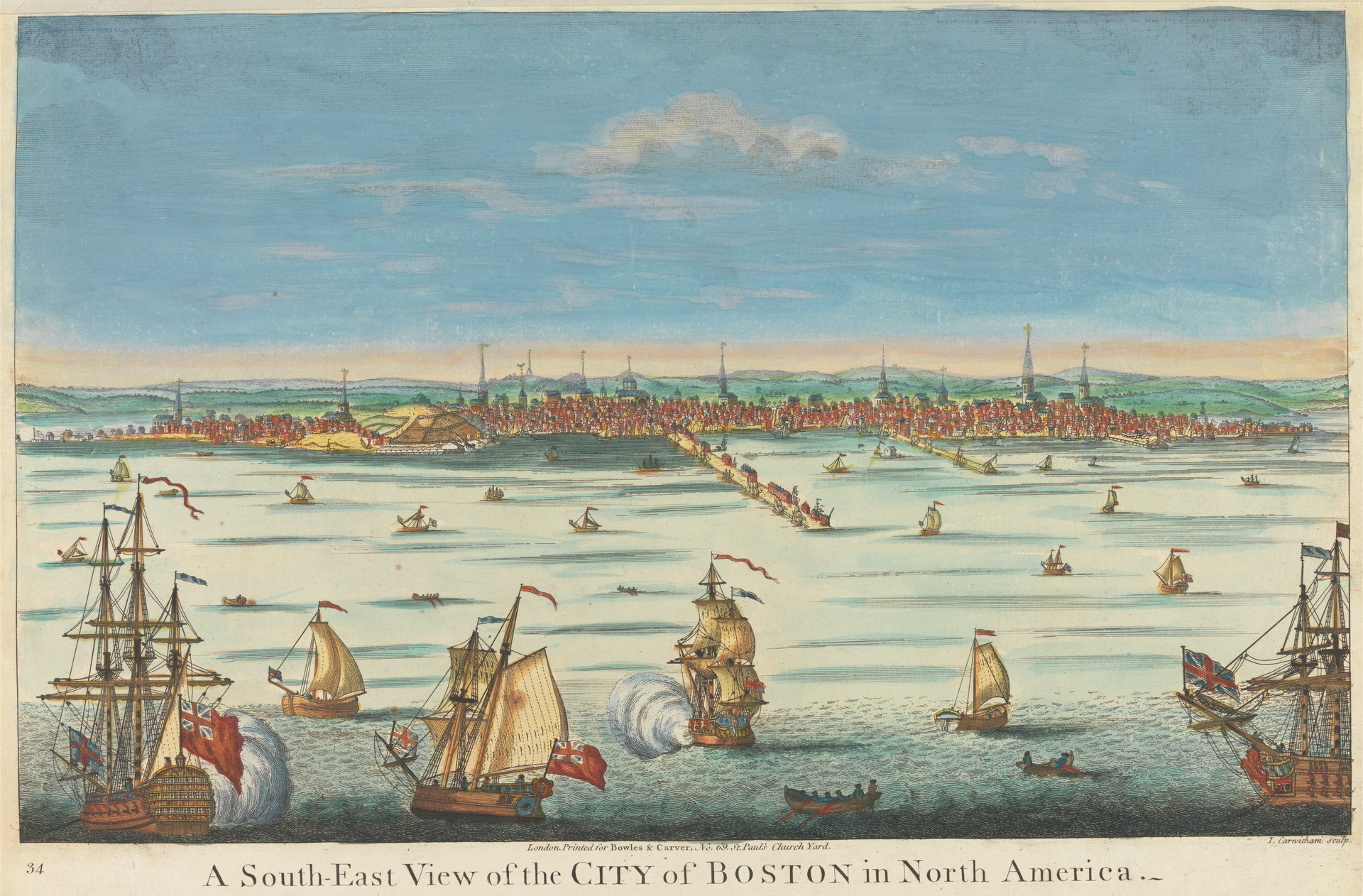

“A South-East View of the City of Boston in North America,” by J. Carwitham after an unknown artist. Hand-colored engraving, circa 1720 – 1740.

In 1721, smallpox had a long incubation period and was transmitted aboard a ship from Barbados stopping in Boston before it traveled on to Great Britain. Given the thriving transatlantic trade at the time, people, goods, and germs moved constantly between Europe, Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and North America. Disease outbreaks were common.

International airline travel today has perhaps accelerated the speed at which diseases can travel, but the spread of diseases to the Athenian Empire during the Peloponnesian War, across the Roman Empire, or from Asia through medieval Europe with the Black Death demonstrates that disease has spread because of travel and trade since ancient times.

When the ship docked in Boston, one of the sailors disembarked and spread smallpox unwittingly to the part of the population that did not have immunity from the previous outbreak a generation before. Once the victim of smallpox was symptomatic and discovered, the town authorities went into action.

The person immediately received what medical care there was at the time and quarantined. Boston harbor was closed to trade, and the ship was quarantined. More than one thousand people fled from the city in terror and could have possibly infected people in other places. Most of the businesses soon shut down, and congregants flocked to their different churches for spiritual relief.

Almost every reader can relate to these experiences of quarantine, fear, business closings, and faith. We may have the technology to work from home, attend online schooling, or watch religious services, but the social, economic, and personal experiences and dislocations were quite similar.

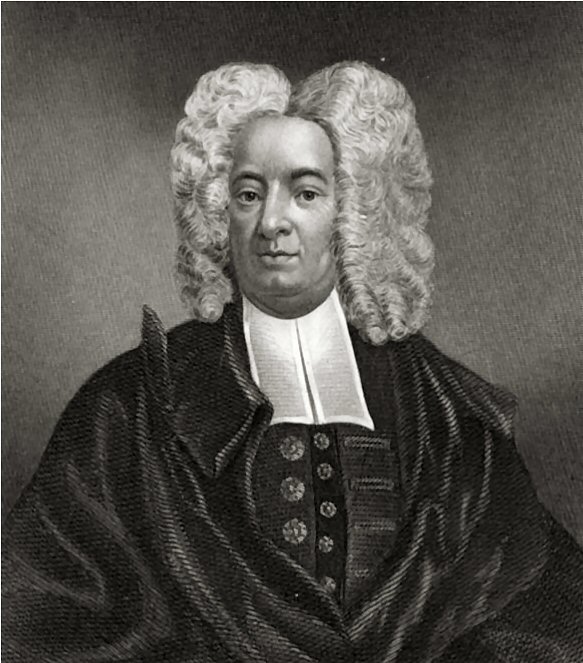

As the disease rapidly spread and Bostonians cared for loved ones while practicing an early version of “social distancing,” an unlikely person named Rev. Cotton Mather decided inoculation should be tried. Perhaps known today more for his role in the Salem Witch Trials, Mather was a man of the Enlightenment who embraced the latest discoveries of the Scientific Revolution and was a member of the British Royal Society. He learned about the inoculation procedure from speaking with his slave who received it in Africa and from reading an article in the Royal Society’s journal describing the practice in the Middle East.

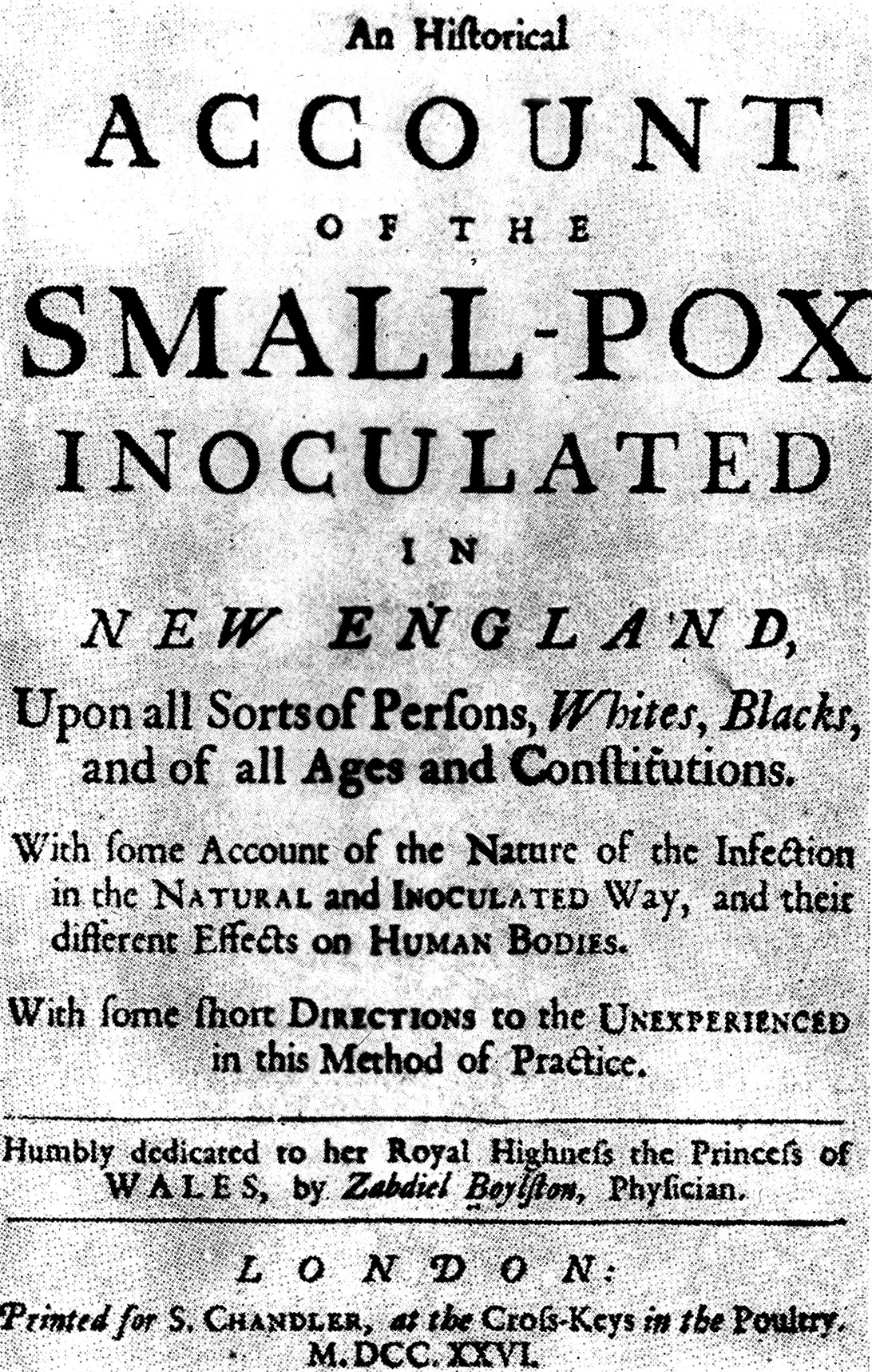

Mather and one physician, Dr. Zabdiel Boylston, decided to give it a try to save lives but encountered significant resistance from the doctors of Boston. They could not understand why one would want to purposefully give the disease to uninfected people. Moreover, the Puritan physicians said it was God’s will that people were getting sick and not to be contested. Finally, they made racist arguments against the procedure because Mather openly admitted he learned about it from his slave.

We should not be surprised at the furor over inoculation. While several pharmaceutical companies race for a vaccine today, talking heads in the media, citizens on social media, and government officials offer up their rival claims for the best path forward and solutions to the crisis.

During the height of the epidemic in the summer of 1721, the death toll began to mount, and individuals were often overwhelmed by grief and concern for their loved ones and their own lives as well as their futures. They anxiously awaited the dreaded arrival of the telltale symptoms.

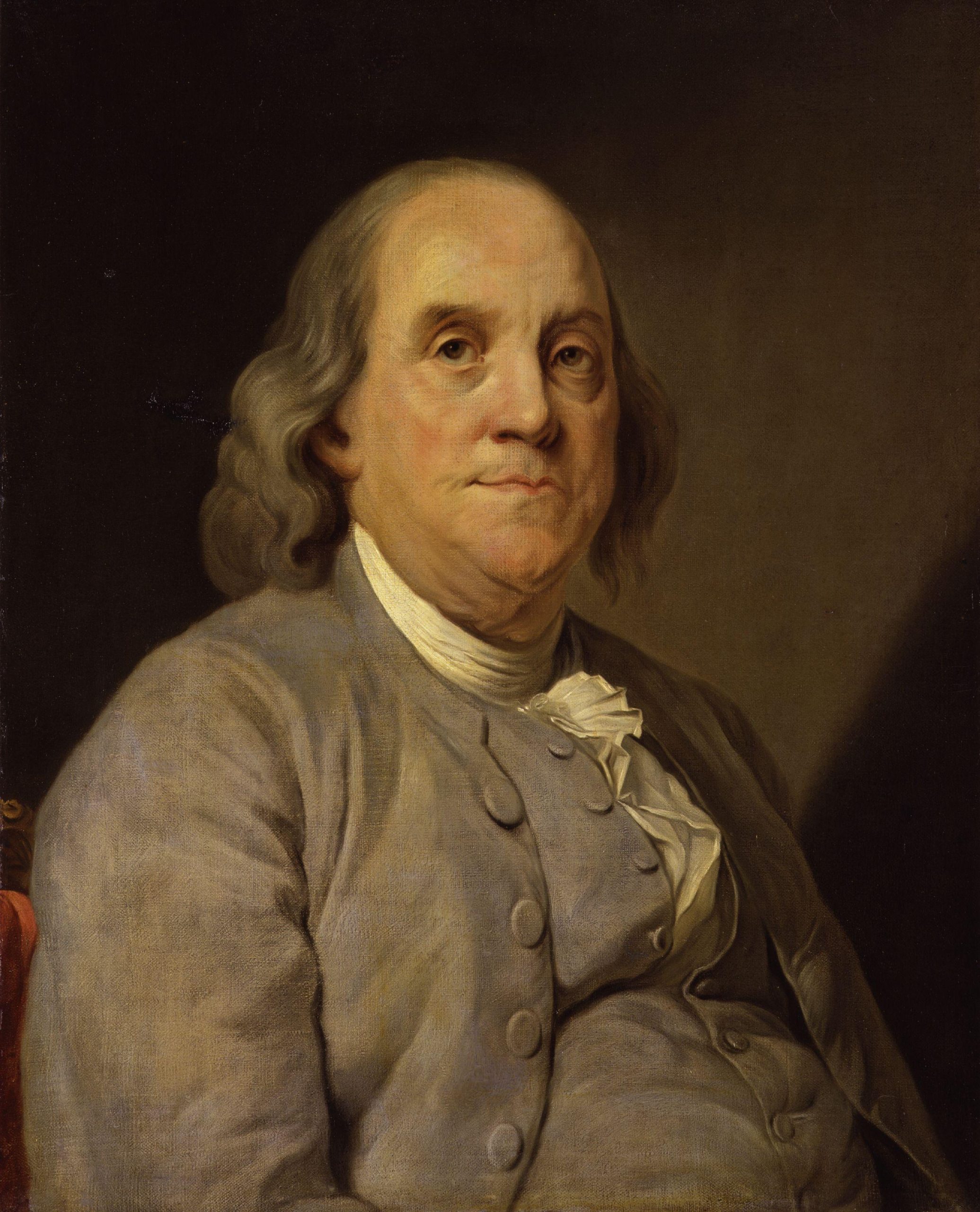

Even in the midst of social breakdown and personal suffering, Benjamin Franklin and his brother, James, introduced a third newspaper into the highly literate city of Boston. Rather than a source of succor or official news that might help the citizens, the Franklin brothers started an anti-inoculation newspaper. They published vitriolic, satirical attacks on the procedure and its practitioners, setting off a firestorm of debate and anger.

Today, while many are remaining positive and the media is responsibly attempting to keep people informed, it would be naïve not to acknowledge the bitter social media venom spewed by many and the partisan recriminations, accusations, and blame passing back and forth. The Corona Virus crisis has generated plenty of twenty-first century virtue-signaling and memes, but the coarseness of the debate is hardly something new.

In 1721, the government provided wood to the poor with the oncoming chill of autumn among other services. That seems like a drop in the bucket compared to trillions of dollars of government relief, unemployment checks, or dropping interest rates and other measures to bolster an economy plunging into recession, but the principle is much the same. In both cases, civil society and neighbors helping each other also played a crucial role in getting through the crisis.

Eventually, the disease ran its course through the population and expired. About 1,000 people died out of a total number of cases totaling more than 6,000, which is a rate one would expect. Mather and Boylston proved that inoculation was an efficacious practice and had a death rate of only 2-3 percent. The controversial practice soon became widespread and was used on the Continental Army by General George Washington.

That winter, businesses opened again, ships returned to the harbor, social relations returned to normal, people walked freely through the streets without fear, believers went back to church. While their lives may have been forever changed in large and small ways, the people endured, and normal life returned again.

It will for us too.

INTERESTING FACTS

Native Americans, having no prior exposure or immunity to European diseases, were severely impacted by smallpox epidemics in the “New World,” of which there were many. As one of Europe’s most deadly diseases, smallpox absolutely devestated many Native American tribes.

“The Pox and the Covenant: Mather, Franklin, and the Epidemic that Changed America’s Destiny,” by Tony Williams, 2010.

Peloponnesian War: (431–404 BCE) A war fought between the two leading city-states in ancient Greece, Athens and Sparta. Each stood at the head of alliances that, between them, included nearly every Greek city-state. The fighting engulfed virtually the entire Greek world, and it was properly regarded by Thucydides, whose contemporary account of it is considered to be among the world’s finest works of history, as the most momentous war up to that time. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

A mezzotint portrait of Rev. Cotton Mather by Peter Pelham, circa 1700.

The Scientific Revolution was a drastic change in scientific thought that took place during the 16th and 17th centuries. Science became an autonomous discipline, distinct from both philosophy and technology, and it came to be regarded as having utilitarian goals. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

“An Historical Account of the Small-Pox Inoculated in New England Upon all Sorts of Persons, Whites, Blacks, and of all Ages and Conditions,” by Dr. Zabdiel Boylston, Physician, 1726.

Oil portrait of Benjamin Franklin by Joseph Siffred Duplessis, 1778.

Enjoy this article? Please consider supporting St. Luke’s with a donation!

Works Referenced

Williams, Tony, “The Pox and the Covenant: Mather, Franklin, and the Epidemic that Changed America’s Destiny,” 2010: https://www.amazon.com/Pox-Covenant-Franklin-Epidemic-Americas/dp/1402260938

About the Author

Tony Williams is a Senior Teaching Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute. He is the author of six books on the American founding including Pox and the Covenant and Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America. He has been a frequent lecturer at St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum.