Last week, we shared a refresher article produced by the Jamestown Yorktown Foundation on our Facebook Page entitled, “What was the first year like at Jamestown?” This brief article re-introduced the many obstacles faced by the early settlers of the Jamestown Colony. Hostilities between the Englishmen and the local Native Americans led to devastating squirmishes. Hunger and disease plagued the colonists, dramatically raising the death toll. The Englishmen, inexperienced in surviving in this new wilderness, fell ill with terrible diseases often caused by their poor water supply. Many experienced salt poisoning, dysentery, typhoid, or even a mixture of these. Furthermore, they unknowingly arrived during a significant drought which further degraded their water supply and quickly led to food shortages and desperation. The list of obstacles facing Jamestown Colony is a long one and even includes the questionable work ethic of the first settlers.

For the purposes of this blog, we will be focusing on illness and the medical obstacles faced by early Jamestown. In 1607, medical practice still recognized the Miasma Theory which essentially blamed “bad air” and foul smells for the spread of disease. Though the theory is obsolete now (replaced by Germ Theory in the late 19th century) it had some merit because removing the causes of foul odors typically meant the removal of bacteria. Not understanding the true cause of disease (bacteria, germs, viruses, etc.), medical practitioners were accidentally removing some of the bacteria that was causing rampant illness, especially in areas with compromised water supply. Unfortunately, we know today that the Miasma Theory was overall inaccurate and ineffectual. In summary, though many medical instruments and practices at the time are what our modern medical system is built on, the Jamestown colonists were essentially practicing and experiencing ineffective triage medical care in a hostile and non-sterile environment.

We can see examples of this by inspecting the archaeological findings of Historic Jamestowne. In 2003, evidence of early surgery was discovered at Jamestown Colony during the archaeological investigation of a ditch that likely once surrounded the western bulwark of the fort. A section of skull was found with three distinct marks from a medical instrument called a trepanning saw. A trepanning saw is used to cut a round plug from the skull with the intention of relieving pressure from brain swelling or fluid buildup within the cranial cavity. In this particular case, the evidence of three failed attempts at trepanation suggests the person using the trepanning saw was inexperienced, picking the thickest part of the skull to attempt the procedure. Unfortunately, the procedure failed and the patient, whose skull demonstrates evidence of at least two mortal blows to the head, did not survive. However, this may have been an important learning experience. The skull fragment discovered in the bulwark was cut from the cranium in what appears to have been an autopsy. This autopsy would have allowed the colony’s surgeons, physicians, apprentices, etc. to identify why the procedure failed (i.e. they were attempting to cut through one of the thickest sections of the skull) and use this knowledge to potentially complete successful measures in the future.

Surgically-Marked Skull Fragment from the collection of Historic Jamestowne, located in the Archaearium, Object # 03067-JR.

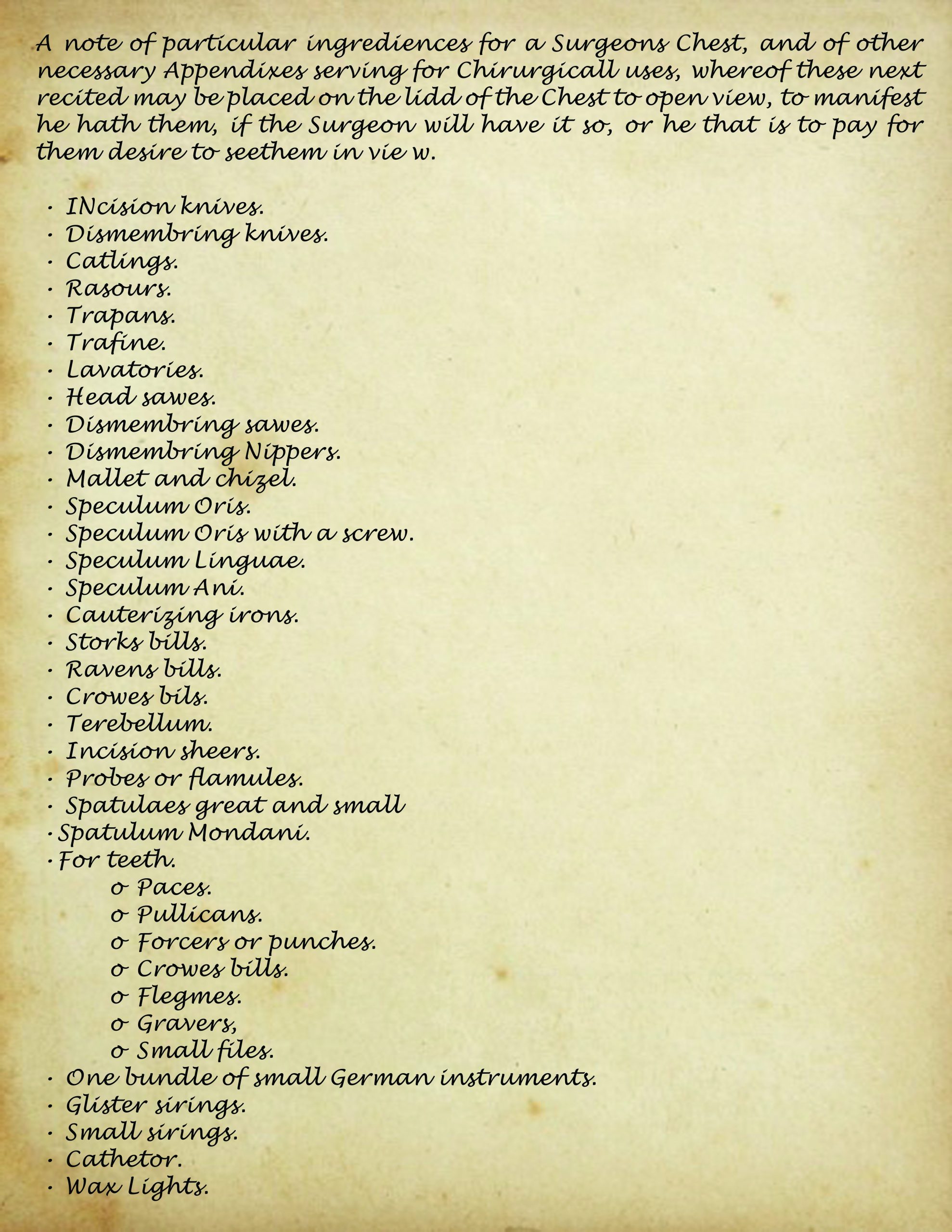

There is documentation of an order for a surgeon’s chest to be sent to Jamestown within the records of the Virginia Company of London. In 1609, John Woodall sent a fully-stocked surgeon’s chest along with an assistant who was expected to report back with further needs. John Woodall was a Barber Surgeon whose experience as a surgeon in the army early in his career likely provided some insight into the needs of surgeons and physicians practicing abroad in unusual circumstances such as aboard ships or as settlers experiencing new and treacherous environments. In 1617, John Woodall published The Surgeons Mate, a manual that quickly become widely used (partially because of his role as Surgeon General for the East India Company). The Surgeons Mate included detailed lists, illustrations, and descriptions of the many tools, herbs, etc. that should or could be included in a surgeon’s chest. Most importantly for the study of medicine at the time, the book was designed to focus on naval medicine and included forward-thinking treatments for scurvy. A portion that focuses on tools to include in a surgeon’s chest from John Woodall’s book is included below:

An excerpt from John Woodall’s book, “The Surgeons Mate,” listing tools for inclusion in a surgeon’s chest.

Many of the medical tools discovered at Jamestown, including the trepanning saw, are illustrated and included in John Woodall’s The Surgeons Mate. It is very likely that many of these tools were included in the surgeon’s chest that was designed and sent to Jamestown by John Woodall in 1609. Other medical findings that likely came in this chest include an Ear Picker for removing earwax, Nippers for amputating fingers, and a Cupping Glass used to cure ailments such as sciatica.

An illustration of surgeon’s tools from John Woodall’s book, “The Surgeons Mate.”

While improved versions of many of these tools are still used today, it is important to understand the conditions that surgeons, barber-surgeons, physicians, and their apprentices would have been working under in early Jamestown. As we can see from the botched trepanation surgery mentioned above, many of these medical professionals may have been inexperienced. At the very least, they were not experienced in some of the procedures they were forced to attempt due to the situations that they, and the colonists, were attempting to survive in. Furthermore, the early colonists did not readily understand what was making them sick and the physicians were not immune. With settlers dying often from diseases that we now understand are caused by poor water supply, it would have been difficult to maintain the collective medical knowledge needed to properly treat the colonists based on the practices of the time. Essentially, Jamestown appears to have been set up for failure in many ways. Instead of failing, it survives to become the first permanent English Settlement in the New World and a building block for the culture that would become the United States of America. How? Why? The answer is complicated and worthy of its own article… which is exactly why we will be exploring these questions in a blog next week. See you then!

INTERESTING FACTS

Miasma Theory: An obsolete medical theory in which diseases were caused by miasmas in the air: poisonous vapors or “bad air” identifiable by their foul smell.

Bulwark: (Noun) A defensive wall. (Oxford Dictionary)

Copperplate engraving by Robert Benard of an 18th century surgeon performing a trepanning operation from Denis Diderot’s Encyclopedia, 1779.

The skull fragment mentioned is not the only example of partial human remains discovered at Historic Jamestowne. They have been found in multiple locations around the fort. Jane, whose skull shows signs of cannibalism during the Starving Time, is perhaps the most famous of these.

Portrait of John Woodall from the Frontispiece of the 1639 edition of, “The Surgeons Mate.” Engraved by George Glover.

Ear Picker from the collection of Historic Jamestowne, located in the Archaearium, Object # 03474-JR.

Cupping Glass from the collection of Historic Jamestowne, located in the Vault, Object # 7890-JR.

Sciatica: (Noun) Pain affecting the back, hip, and outer side of the leg, caused by compression of a spinal nerve root in the lower back, often owing to degeneration of an intervertebral disk. (Oxford Dictionary)

An Interesting Connection: Dr. Gabrial A. D. Galt (1834-1908) is buried in the Ancient Cemetery at St. Luke’s outside the east wall of the historic church. Dr. Galt is perhaps best known for his creation of the Galt Trephine in 1860. Galt’s version of the surgical tool called a trephine featured a truncated cone with spiral teeth. A trephine is similar to a trepanning saw in that it is designed to remove a disc of bone from the skull. The minor changes to the trephine suggested by Dr. Galt were designed to stop the tool from entering the cranial cavity during surgery. There is still some controversy today over who truly designed this version of the trephine. In response to accusations by other medical professionals who claimed Galt was not the original creator, Dr. Galt publicly apologized saying that the idea was new to him and one he thought was original at the time of the public presentation of his trephine design. Despite the controversy, this version of the trephine is still referred to as the Galt Trephine today.

Photo of a Conventional Crown Trephine (left) and a Galt Trephine (right) from the collection of the Dittrick Museum (acc. 6760 and 7256), both circa 1875. Photo is Figure 117 in the book, “American Surgical Instruments: An Illustrated History of Their Manufacture and a Directory of Instrument Makers to 1900,” by James M. Edmonson, Ph.D., 1997.

Enjoy this article? Please consider supporting St. Luke’s with a donation!

Works Referenced

Jamestown Rediscovery: Historic Jamestowne, “Surgically-Marked Skull Fragment,” Object # 03067-Jr, https://historicjamestowne.org/collections/artifacts/surgical-skull-fragment/

Jamestown Rediscovery: Historic Jamestowne, “Trephination at Jamestown,” Video, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=194&v=XafAEZkPjgI&feature=emb_title

Jamestown Rediscovery: Historic Jamestowne, “A Ditch and its Treasures,” https://historicjamestowne.org/archaeology/map-of-discoveries/west-bulwark/

Jamestown Yorktown Foundation, “What was the first year like at Jamestown?,” https://www.historyisfun.org/learn/learning-center/what-was-the-first-year-like-at-jamestown/

“Records of the Virginia Company of London,” Edited by Susan Myra Kingsbury, A. M., Ph. D., Volume III Documents I, Library of Congress, http://www.virtualjamestown.org/exist/cocoon/jamestown/virgco/b002245360

Woodall, John, “The Surgeons Mate,” Originally published in 1617, https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A66951.0001.001/1:8?rgn=div1;view=fulltext

About the Author

Rachel Popp, Former Education Coordinator, worked at St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum in some capacity since Fall 2015 when she began researching the site as a student at Christopher Newport University (CNU). At CNU, Popp studied history and minored in Childhood Studies, graduating with a Bachelor’s in History in May 2016. Rachel Popp became the Education Coordinator at St. Luke’s a few months later. She grew up in the outskirts of Virginia Beach, close to the North Carolina Border. Growing up in Virginia, a state with such a profoundly rich history, encouraged Popp’s interest in history from the time that she was young. Today, Rachel Popp spends her spare time diving deeper into the Virginia Museum Community by partnering with, and participating in, organizations such as Virginia Emerging Museum Professionals (Hampton Roads Ambassador), Peninsula Museums Forum (President), and the Virginia Association of Museums (Member).