During the Summer of 1950, Wythe County, Virginia experienced a polio outbreak that quickly spread, becoming one of the worst per capita epidemics of polio in U.S. History. The death rate reached almost 10% that summer, roughly twice the country’s average at the time. Despite medical advancements since then, including the creation of the first effective polio vaccine in 1952, the reason why Wythe County experienced such extreme cases of polio remains a mystery. Despite a limited understanding of what caused the polio epidemic, Wythe County is still recognized today for the unflappable calm and courage the community showcased during the 1950 “summer without children.” How did this particular community become touted as “the town that kept its head”? What set Wythe County apart from other areas with similar epidemics? Open and clear communication appears to have been key.

When it comes to public health concerns, it seems that the public is often the last to know. This was not true for the 1950 polio epidemic in Wythe County, Virginia. This does not mean there was a conscious and purposeful spread of information during the very beginnings of the epidemic. Instead, it is more likely the small-town atmosphere of 1950 Wythe County was very conducive for sharing information (and perhaps spreading rumors), preventing any potential control of facts by local officials. Furthermore, the first confirmed case of polio that summer impacted the family of Jim Seccafico, arguably a local celebrity and someone that many Wythe Countians would have known personally or known of, locally sensationalizing the first case. In 1950, Jim Seccafico was the second baseman for the Statesmen. Baseball had become a popular pastime and many people living in Wythe County and the surrounding areas could be found at the local games of The Statesmen, a semi-professional baseball team based in Wytheville, Virginia at the time. Unfortunately, the popularity of these baseball games may have contributed to the initial spread of the polio virus as the first known case was of John Seccafico, the 20-month-old son of Jim Seccafico. In a 2019 news article, John Seccafico’s widow notes that none of Jim Seccafico’s teammates had children at the time so “Johnny” was often cuddled and passed around during the games, adored by the team and their fans. The family remains suspicious that this may be how John Seccafico was exposed to the virus in the first place. More polio cases quickly arose and local authorities soon wondered if they were experiencing the beginnings of an epidemic.

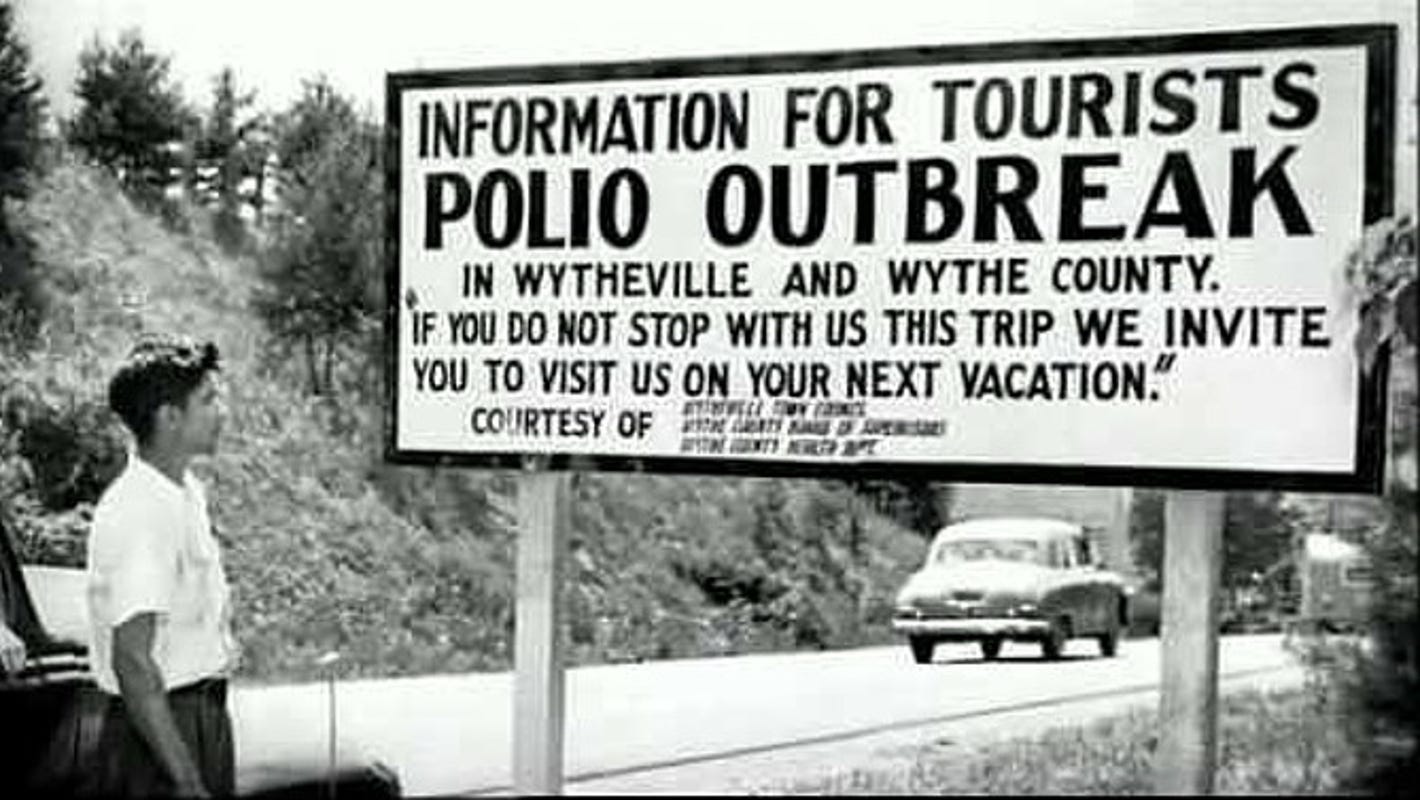

Purposefully or not, the community was aware of polio cases beginning to spread through Wythe County. Instead of trying to squelch information, local town officials built on this, maintaining an open line of communication with their community, with assisting outside agencies, and even with tourists traveling in the vicinity. Wythe County’s convenient location where Route 11 and Route 21/52 intersect made it a popular stop for travelers and truckers. In 1950, Wytheville was a thriving tourist town during the summer, the cool mountain air and small-town charm appealing to those escaping the sweltering heat of states further south. Concerned about the potential exposure of tourists to their growing polio outbreak, the Wytheville Town Council unanimously agreed to put up signs along the county limits, essentially warning travelers not to stop. The signs read, “Information for Tourists: Polio Outbreak in Wytheville and Wythe County. ‘If you do not stop with us this trip we invite you to visit us on your next vacation.’ Courtesy of Wytheville Town Council, Wythe County Board of Supervisors, and Wythe County Health Department.”

One of the signs posted along the Wythe County limits, discouraging tourists from stopping.

Much like we are seeing in the news today, there was some pushback to the creation of these signs. Many motorists driving through the area would roll up their windows, preferring to sweat in the heat of cars that did not have air conditioning over breathing too much of Wythe County’s air. At the time, this would have seemed like an important precaution as it had not yet been determined how the poliovirus spread. While it was important to inform tourists, truckers, and motorists of the health risks of stopping in Wythe County for their own safety, the signs publicized the polio outbreak in a way that caused a certain level of distrust and paranoia among those passing through. As can be expected, this was not appreciated by the local business community whose economic prosperity depended on the influx of visitors who typically came during the summer months.

Carter Beamer, the Town Manager for Wytheville in 1950, notes in an interview included in the book A Summer Without Children, that the signs were torn down within a few days of their installment. The Town Council had them put back up where they stayed for roughly 3 weeks before being taken down once again and disappearing altogether. Many people within the community knew the signs were scheduled to be taken down around the time they disappeared (August 19, 1950) and so the Town Council did not replace them. The destruction and later disappearance of the signs became their own mystery. Despite a $100 reward offered to the community for information and publicized in the local newspaper, the Town Council and Board of Supervisors never found out who had tampered with the signs. Despite the pushback, these signs created a certain level of local quarantine, preventing the potential spread of polio, particularly important at the time as how the virus spread was unknown.

The local newspaper became incredibly important to the dissemination of accurate information within the community, not only through the newspaper but also through signage posted outside of the news office itself. The Southwest Virginia Enterprise, Wythe County’s newspaper at the time, had an office on Main Street. The editor, James “Jim” A. Williams, posted a bulletin board outside of the newspaper’s office which was updated daily (sometimes more) with the number of polio cases. The bulletin board was clearly displayed on Main Street and Jim Williams remained dedicated to updating it as often as possible with the most recent and accurate numbers. This same spirit can also be seen in the Enterprise’s newspapers. The July 28, 1950 edition touted the headline, “Get The Facts – Please Don’t Spread Rumors,” encouraging the public to prevent the spread of misinformation via the rumor mill. This headline also implied a promise that the Enterprise would continue to do its best to provide these facts for the public.

In A Summer Without Children, a 1950 Wythe County local named Alex Crockett comments on the impressive work of James A. Williams and The Enterprise during this timeframe saying, “He [James Williams] should have been awarded a Pulitzer Prize or something for his handling of the epidemic; he seemed to sense almost from the beginning the seriousness of the situation and to be aware at the same time of the difficulty of keeping things in proper perspective. He was active also in the Chamber of Commerce. You might think… as in the movie, “Jaws,” that the Chamber and city officials would have rushed to hush things up. Well, that was never the case here. Mr. Williams felt from the beginning that getting out the correct information was the most important task that the newspaper had, and he was very scrupulous in reporting the cases just as they occurred. At the same time, there were all sorts of rampant rumors about ‘what in the world was going on here’ and what the possible consequences might be. He did his best to deal with those rumors and keep things in some kind of perspective.”1

With the town essentially closed and all large community gatherings cancelled, the radio became an important source of entertainment and information for both adults and children in Wythe County. A decently new radio station at the time, WYVE became a lifeline for the community. Realizing that children within the county were stuck at home, WYVE created new segments designed for kids that consisted of on-air stories and quizzes whose answers were shared on the radio the next day. Mrs. Jean Kitts Lester, recalling her childhood in Wythe County during the polio epidemic, recounted the importance of the radio in her family’s daily routine saying, “The radio was just wonderful. That was our contact to the outside world. Our parents kept nothing from us because we’d sit around the radio and listen to see how many new cases there were. The radio was our connection to life.”2 Thus, radio’s popularity within the community skyrocketed and WYVE responded positively by creating innovative programs and informative news broadcasts to accommodate their changing role. Furthermore, the WYVE staff proved passionate about their work and their community, working for 2 to 3 months at half pay when the station began to have financial problems due to a lack of interest in radio advertising slots. While this situation clearly was not ideal, it is important to note that the WYVE staff were going above and beyond despite the negative impact the polio epidemic was having on their personal and professional lives.

By mid-August, Wythe County began to finally experience a decrease in polio cases. By the end of the epidemic, 189 cases had been officially reported though experts are confident there were more cases unreported. The first version of the polio vaccine was not ready for public consumption until 1954 despite the race for a “cure.” Today, Wythe County continues to embrace this part of their history with a permanent exhibit on the 1950 polio epidemic in Wytheville’s Thomas J. Boyd Museum.

INTERESTING FACTS

Polio: (Noun) an infectious disease especially of young children that is caused by the poliovirus. Individuals infected with the poliovirus are often asymptomatic. In approximately 25% of cases, polio presents as a mild to moderate illness marked by headache, fever, sore throat, vomiting, and fatigue. Polio affects the central nervous system only infrequently with inflammation and sometimes destruction of the motor neurons in the gray matter of the spinal cord and brain stem. Central nervous system involvement results in temporary or permanent muscle weakness or motor paralysis especially of the limbs and typically the legs. Polio may become life-threatening when paralysis affects the muscles involved in breathing and swallowing. (Merriam-Webster Dictionary)

Photo of young John Seccafico with a nurse, 1950.

Though John Seccafico’s contraction of polio altered the course of his life, he lived a long and accomplished one, passing away recently on March 4, 2019. Wheelchair-bound from his experience with polio, he remained dedicated to his education during a time when many university buildings were not physically accessible. He and his wheelchair often had to be carried up the steps of education buildings and despite these challenges, including his inability to pick up a textbook, he earned a Master of Arts from Seton Hall University and Master of Social Work from Rutgers University. John Seccafico became a licensed clinical social worker and a licensed marriage and family therapist. He cared deeply about his clients and worked hard to provide affordable and accessible mental health care. John married Alice, the love of his life, in 1989 and proved to be a loving stepfather to Alice’s children and later, an adoring grandfather. John Seccafico was a remarkable person whose accomplishments and loving spirit far surpassed his role as the first identified case in the 1950 Wythe County polio epidemic.

Polio Wasn’t “Whites Only” But Some of the Hospitals Were: Segregation was still legal and part of everyday life in 1950 Wythe County. Unfortunately, this would have a particularly severe impact on the care of African American children who came down with polio during the epidemic. The closest hospital (Roanoke, 80 miles away) was “whites only” and refused to reconsider their policy despite the growing epidemic. The ambulances were forced to drive 300 miles (one-way) to St. Philip’s Hospital in Richmond, which was a particularly grueling trip due to the lack of air conditioning in vehicles at the time. When Betty Cook fell especially ill, Dr. Charlie Graham begged Roanoke Hospital to admit her for care, to no avail. Her mother, Mrs. Sammie Cook, recalls the long drive and sweltering heat, admitting that she has always wondered if these difficult conditions led to the paralysis of Betty’s jaw.3

Lee Hale: Though not a victim of the 1950 polio epidemic, Lee Hale garnered fame in the “Guiness Book of World Records” when he was listed as the man who lived the longest in an iron lung. Hale was a citizen of Wythe County who contracted polio in 1944 and went on to successfully live in an iron lung for 32 years.

Photograph of Lee Hale in an iron lung.

Enjoy this article? Please consider supporting St. Luke’s with a donation!

Works Cited

1) A Summer Without Children: An Oral History of Wythe County, Virginia’s 1950 Polio Epidemic, Town of Wytheville Department of Museums, 2005, pg. 53.

2) A Summer Without Children: An Oral History of Wythe County, Virginia’s 1950 Polio Epidemic, Town of Wytheville Department of Museums, 2005, pg. 47.

3) A Summer Without Children: An Oral History of Wythe County, Virginia’s 1950 Polio Epidemic, Town of Wytheville Department of Museums, 2005, pg. 40.

Works Referenced

A Summer Without Children: An Oral History of Wythe County, Virginia’s 1950 Polio Epidemic, Town of Wytheville Department of Museums, 2005.

PBS, The Polio Crusade, Season 21, Episode 2, aired 31 March 2020: https://www.pbs.org/video/american-experience-the-polio-crusade/

Rothrock, Millie, “Man at center of 1950 Wythe County polio epidemic dies,” The Wytheville Enterprise, 18 March 2019: https://www.roanoke.com/news/virginia/man-at-center-of-1950-wythe-county-polio-epidemic-dies/article_207907ed-b8ed-5b16-9011-cdc36f4ee268.html

Spraker, Timothy Jacob, Ghost Town Tension: Post-War Public Health and Commerce in a Rural Virginian Polio Epidemic, 1950, Thesis, 2012: https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/bitstream/handle/10919/78105/etd-05112012-102816_Spraker_TJ_T_2012_2.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Tennis, Joe, “Polio outbreak created mystery, fear and quarantines,” Bristol Herald Courier, 24 August 2013: https://www.heraldcourier.com/news/polio-outbreak-created-mystery-fear-and-quarantines/article_c8443f42-0d2f-11e3-93e6-0019bb30f31a.html

A Note to Readers

In reading A Summer Without Children as part of my research for this blog, I was struck by the similarities between what Wythe Countians were experiencing during the 1950 polio epidemic and what we are experiencing today during our current Covid-19 pandemic. The book, which mainly consists of a string of oral stories from those who lived in Wythe County during the 1950 epidemic, mentions people wearing bandanas over their faces and no-contact grocery shopping where grocers would bring the groceries out and leave them on the sidewalk a few feet away for the customer to pick up once they had retreated. People talked about the closing of schools, churches, the movie theater, and the local pool. I could go on. Though not the point of this particular blog, I think it is important to note that many people, especially those that work in museums and other history-related fields, feel that history is important to learn from because it so often repeats itself. Throughout this blog series, we have seen history repeat itself in many ways and many forms. What have we learned from the past that can inform us in our current pandemic? Will we, like Wythe County during the 1950 polio epidemic, be known for keeping calm and supporting our community? I hope this blog series has encouraged you to ask your own questions and perhaps sparked your own interest and research. Thank you for taking this journey through history with us.

About the Author

Rachel Popp, Former Education Coordinator, worked at St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum in some capacity since Fall 2015 when she began researching the site as a student at Christopher Newport University (CNU). At CNU, Popp studied history and minored in Childhood Studies, graduating with a Bachelor’s in History in May 2016. Rachel Popp became the Education Coordinator at St. Luke’s a few months later. She grew up in the outskirts of Virginia Beach, close to the North Carolina Border. Growing up in Virginia, a state with such a profoundly rich history, encouraged Popp’s interest in history from the time that she was young. Today, Rachel Popp spends her spare time diving deeper into the Virginia Museum Community by partnering with, and participating in, organizations such as Virginia Emerging Museum Professionals (Hampton Roads Ambassador), Peninsula Museums Forum (President), and the Virginia Association of Museums (Member).