The 16th and 17th centuries saw horrific conflicts spawned by the religious disputes known as the Reformation. By the 18th century, these conflicts switched to disputes of a more economic and political nature. Most of us don’t think of the American Revolution as a religious conflict and yet religion was a major bone of contention throughout the engagement.

This all seems rather odd when you consider that the American Revolution was more of a civil war than a traditional revolution. English people were fighting English people. War was waged by people who had a shared language, a shared history and, to a large degree, similar religious viewpoints. The disagreements over religion were no more acute between American Colonists and the Mother Country than they were between citizens living in England.

When we consider the conflicts that caused America to declare independence, we often think of taxes. The famed slogan attributed to James Otis; “no taxation without representation,” is usually considered the main rift between King George III and his subjects across the Atlantic. We recall the various acts that placed duties on items like tea and stamps but, in reality, the average Colonist paid less in taxes than their counterparts in London. It is the last part of the slogan that comes closer to achieving the true sticking point: Representation.

The Colonists cared more about their lack of involvement in making decisions than in the actual decisions themselves. Many of the decisions that the Colonists were most concerned about regarded religion. In the Colonies, where the Established Church of England was dominant, taxes were levied to pay for the services of ministers and the work of the church. Even English subjects from a different religious tradition were subject to those same taxes. If you wanted to hold public office in many of the Colonies, you had to be part of the Church of England. But no Bishops were ever sent over to the Colonies which created a shortage of clergy and a feeling that their spiritual care was less important than citizens living in England.

In the early 17th century, the Great Awakening spurred many Colonists to believe that the most important relationship in faith was between God and the individual and that no government should be given authority over that relationship. Many colonial clergymen were known to give sermons insisting that fighting against tyranny was the duty of Christian people. Not all Colonists shared this ideal.

The clergy were largely loyalist when hostilities broke out in April of 1775 and many returned to England rather than break their oath of loyalty to the Head of the Church, King George III. If God appointed Kings and other authority figures, a dominant belief at the time, then how could someone support the overthrowing of that divinely elected authority? Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense” reads much like a sermon on the Exodus story, how God is want to deliver oppressed people. George Washington enlisted the help of chaplains to help keep the morals of the soldiers respectable as well as encouraging them to hold fast to their enlistment obligations. Both sides were convinced that God was present during this conflict and, of course, on their side.

During the American Revolution, the Anglican churches were largely in disarray as taxes were no longer collected and church properties were forfeited. With clergy few and far between, the Church of England in the U.S. was on life support. In 1783, the Treaty of Paris ended the war and the United States officially became a sovereign nation. What was a good Anglican American to do? The first step was to try and find a source for the consecration of Bishops.

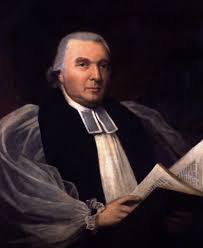

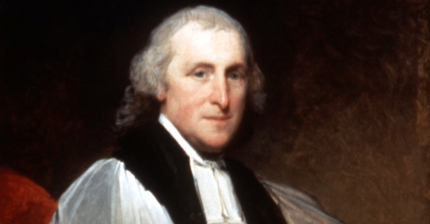

Samuel Seabury was elected by the Anglicans living in Connecticut, but bishops in England were precluded from consecrating anyone who did not take an oath of loyalty to the King. Seabury sought and was granted his consecration through the nonjuring line in Scotland in 1786. Shortly thereafter, Parliament granted exemptions for Anglicans living outside of Great Britain and William White, Samuel Proovost, and James Madison were all made bishops through the Archbishop of Canterbury for Pennsylvania, New York, and Virginia respectively. Thus, the Protestant Episcopal Church in America was born.

The fledgling church had an uphill battle. Americans largely had a distrust for all things British and the close connection between Anglicans in America with those in England was considered suspect. Episcopal priests had to teach their parishioners the joys of tithing as taxation was no longer imposed. Some northern states held on to the ideals of establishment well into the 19th century but, by in large, the notion of separating church and state was taking hold.

Unfortunately, much of the early history of the Protestant Episcopal Church is clouded because of the confusion of those rocky times. Bishop William Meade, the third Bishop for the Diocese of Virginia, wrote in 1857; “Had I kept a diary for the last fifty years, and taken some pains during that period to collect information touching the old clergy, churches, glebes, and Episcopal families, I might have laid up materials for an interesting volume; but the time and opportunity for such a work have passed away. The old people, from whom I could have gathered the materials, are themselves gathered to their fathers.”1 Bishop Meade’s lament is that of every church historian since that time regarding the challenges and conflicts of the Episcopal Church in America coming into its own.

What we do know is that religion had far more to do with the American Revolution than most of our history classes taught us and new religious bodies like the Protestant Episcopal Church and the Methodist-Episcopal Church were born in the soil of the new republic.

(Above) Portrait of Bishop Samuel Seabury.

(Above) Portrait of Bishop William White.

(Above) Portrait of Bishop Samuel Proovost.

(Above) Portrait of Bishop James Madison.

(Above) Photo of Bishop William Meade.

Enjoy this article? Please consider supporting St. Luke’s with a donation!

Works Cited

1) William Meade (2019-05-01). Old Churches, Ministers and Families of Virginia: Index (Kindle Locations 98-99). J.B Lippincott & Company. Kindle Edition.

Works Referenced

A HISTORY OF THE EPISCOPAL CHURCH Third Revised Edition. Robert W. Pritchard, Moorhouse Publishing. Copyright 2014.

Pulpit and Nation Clergymen and the Politics of Revolutionary America SPENCER W. MCBRIDE University of Virginia Press CHARLOTTESVILLE AND LONDON Copyright 2016.

About the Author

John Ericson is the Outreach Coordinator and a Public Historian for St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum. John holds a degree in History from Roanoke College and a Masters of Divinity from the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg. In addition to John’s role at St. Luke’s, he is the Pastor of Reformation Lutheran Church in Newport News, Virginia. John is married to Oneita Jamerson Ericson, a native of Isle of Wight County, Virginia. They have three sons, Matthew, Thomas, and James, as well as two granddaughters, Carys and Lennon. The Ericsons currently reside in Hampton, Virginia. John has been teaching Reformation History and the Early American Religious Experience for more than thirty years.