As we ring in the New Year here at St. Luke’s we are excited to share our new podcast series covering a wide range of topics based around the early American religious experience with the first episodes available on streaming services now. A survey done in the United States in 2017 found that 50% of households consider themselves consistent listeners to podcasts series (Winn, 2021). Additionally, the estimated total number of podcasts available on the top streaming services has risen in the past decade from around 115,000 (Dial, 2012) to now somewhere around 2 million (Molenaar, 2021). This rise of podcasts as a medium for communication and education has been exponential and represents, among other things, a shift in what we believe the best way to experience today’s prevailing ideas may be. In the same vein, we will discuss another important shift in what was believed to be a better way of experiencing the prevailing ideas of Christianity: the emotional revival of faith and preaching known as the First Great Awakening.

For much of the history of Christianity, listening to the sermon given by the minister or preacher was the way to learn more about one’s place in their Christian faith and consequently how they fit in with the prevailing ideas at the time. The First Great Awakening represents a change in how people wanted to receive these ideas in the English Colonies in particular. So what exactly was what is now known today as the First Great Awakening? Put best by Professor Christine Heyrman from the Department of History at the University of Delaware, the Great Awakening, “can best be described as a revitalization of religious piety that swept through the American colonies between the 1730s and the 1770s. That revival was part of a much broader movement, an evangelical upsurge taking place simultaneously on the other side of the Atlantic, most notably in England, Scotland, and Germany. In all these Protestant cultures during the middle decades of the eighteenth century, a new Age of Faith rose to counter the currents of the Age of Enlightenment, to reaffirm the view that being truly religious meant trusting the heart rather than the head, prizing feeling more than thinking, and relying on biblical revelation rather than human reason.” (Heyrman, 2008). Heyrman points out that the sentiments of the First Great Awakening were not exclusive to the colonies, in fact, the movement of evangelism occurring in England brought the Methodist faith to colonial Maryland and Pennsylvania in the late 1760s in the form of Christian societies. By the 1770s the Methodists were some of the most prominent proponents of the core concepts of this movement and provided a lasting structure for them that was lacking by the end of the First Great Awakening. But what were these core concepts and how did they differ from what was taught in sermons before the 1730s?

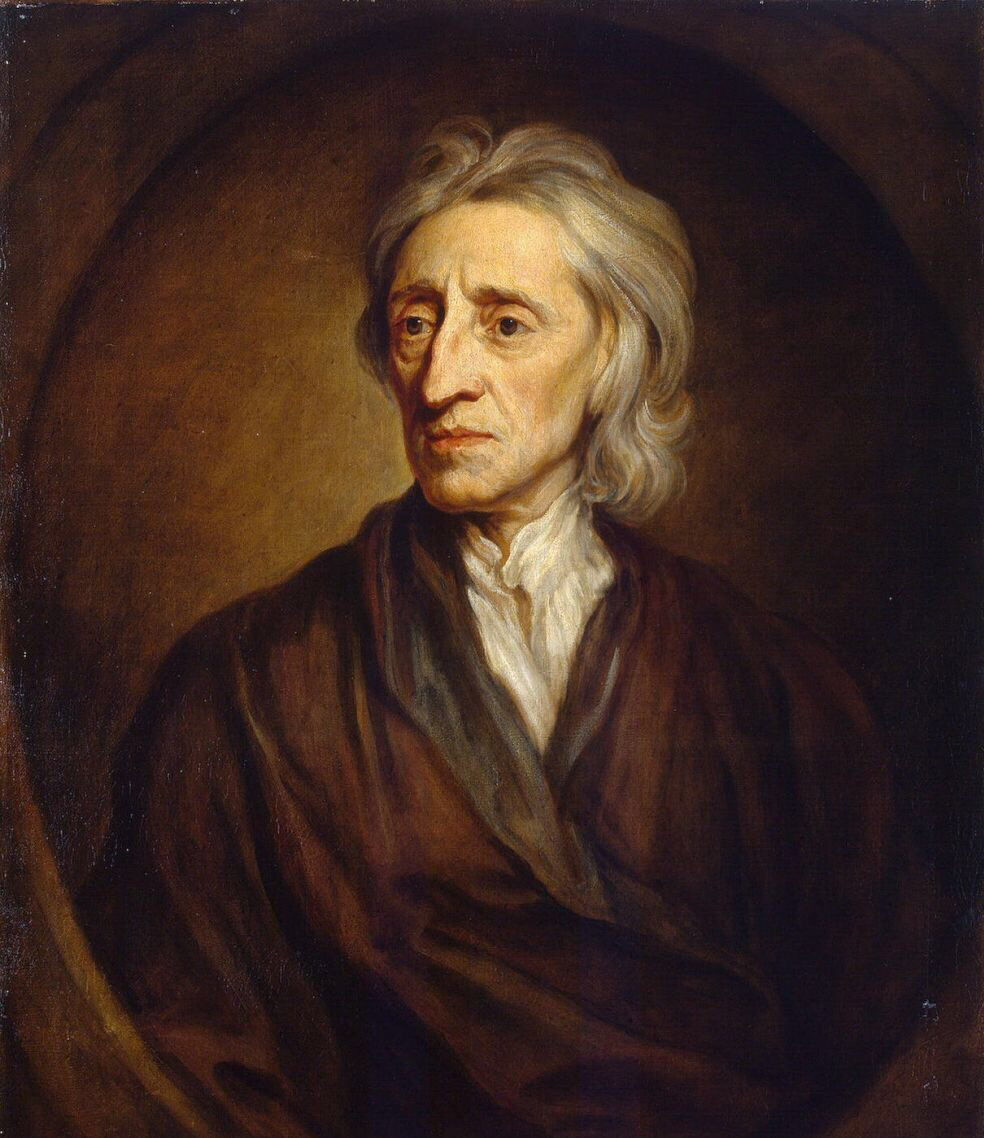

Particularly in Maryland and Virginia, the Church of England dominated the colonies both in establishment and in theological practice. Traditional Anglicanism was guided, in part, by John Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding (Prichard, 2014). In this essay, Locke explains that intellect, i.e. understanding, is the most elevated faculty of the soul and therefore should be evoked for theological belief rather than emotion which only affects short-term decision making. This Age of Enlightenment thinking seemed to be backed by the plethora of scientific innovations and discoveries achieved during this time, so ministers and clergy were urged to use intellectual arguments concerning faith. A prime example of this can be seen in the Church of England’s Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in foreign parts (SPG)’s instructions to their missionaries on how they were to convert non-believers. “IV That the chief Subjects of their sermons be the great Fundamental Principles of Christianity, and the Duties of a sober, rites, and holy Life, as resulting from those Principles.” and later, “IX That in their instructing Heathens and Infidels, they begin with the Principles of Natural Religion, appealing to their Reason and Conscience; and thence proceed to shew them the Necessity of Revelation, and the Certainty of that contained in the Holy Scriptures, by the plainest and most obvious Arguments.” (SPG, 1898). It can be seen that messages of duty, structure, and logical reason are the main focuses for the preaching and converting to the Anglican Church.

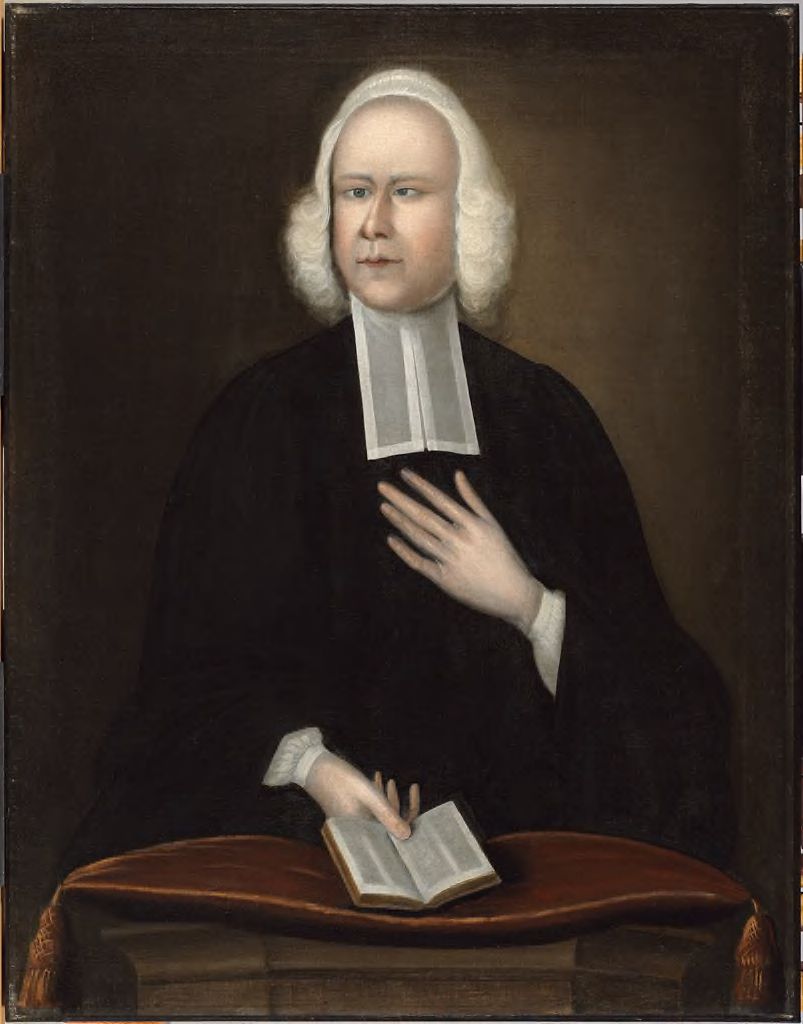

Compare this to a sermon given by Rev. George Whitefield, an Anglican preacher who was a catalyst for the First Great Awakening. Whitefield states, “Then, you could not give me a better proof that you never yet believed in Jesus Christ, unless you were sanctified early, as from the womb; for they that otherwise believe in Christ know there was a time when they did not believe in Jesus Christ.” and earlier states, “And, therefore, if you never felt this inward corruption, if you never saw that God might justly curse you for it, indeed, my dear friends, you may speak peace to your hearts, but I fear, nay, I know, there is no true peace.” (Whitefield, 1906). The purpose of this sermon is to give the parishioners one of the most fundamental ideas to the First Great Awakening, that faith is not achieved justthrough an intellectual understanding of Christianity, but is achieved through feeling its impact on one’s life. Christians were meant to look inward at themselves, be honest about their belief, and have a total conversion in thought, word, and deed. This was called “New Birth” and was at the very core of the First Great Awakening.

While George Whitefield was certainly on the extreme compared to his follow Anglican ministers, the effect of his sermons and the larger movement made a lasting impact on the way, particularly new, clergy taught the faith. They became proponents of the idea of “New Birth” and other ideas brought to the forefront such as small group worship. Whitefield struggled to erect infrastructure to promote the longevity of his ideas but successfully helped pave the way for the introduction of the Methodist Church in the early Republic, an increase of membership in the Baptist Church (both of which were some of the biggest influencers in the Second Great Awakening), and lasting changes to the way the Church of England approached worship, especially in the colonies. Like the modern rise of podcasts representing a shift in how people want to consume new ideas and concepts, the First Great Awakening was a shift in how people wanted to practice their new ideas and concepts in faith. The debate between intellectual and sentimental understanding of faith is one that persists today in Christianity, but one thing is certain: the First Great Awakening persuaded many people that faith was something meant to be closer to the heart than to the head.

Above: A portrait of John Locke, one of the most influential Enlightenment philosophers from the 17th century.

Above: A portrait of George Whitefield, the evangelical minister from the Church of England who was a catalyst for the First Great Awakening.

Above: A portrait of John Wesley, the minister who led the Methodist movement within the Church of England.

Enjoy this article? Please consider supporting St. Luke’s with a donation!

About the Author

Thomas Fosdick has worked at St. Luke’s Historic Church and Museum as a Museum Interpreter since August of 2021. In May of the same year, he graduated from Christopher Newport University with a Degree in American Studies and Political Science while minoring in Leadership Studies. He has been a volunteer and intern with the Mariners’ Museum and Park’s Library Department since January of 2021 and is a member of the Archaeological Society of Virginia. He plans to pursue a Master’s Degree in Maritime Studies starting in August of 2022. Outside of his vocations, he enjoys playing music with his band “Native Love” and spending time with friends and family in and outside of his hometown of Newport News.