One of the questions our Museum Interpreters often receive is, “Who is the most famous person buried in the cemetery?” While there are many notable burials, Henry Mason Day is perhaps one of our most Google-able cemetery residents. As the first president of our 501©3 non-profit organization when it was established in 1953, Henry Mason Day was an important figurehead and a driving force of the 1950s Restoration of the church building.

Despite Henry Mason Day’s wholesome dedication to the restoration of the historic church building now known as St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum, he is still perhaps more known for his involvement in the Teapot Dome Scandal that rocked 1920s America. On April 14, 1922, The Wall Street Journal published an article that began identifying political corruption at the highest level of government. This had begun in 1921, when oversight of government-owned oil reserves was transferred from the U.S. Navy to the Department of the Interior, which was then under the supervision of Albert B. Fall. In turn, Fall accepted bribes from two private businesses to lease them these government-owned oil reserves without government authorization, creating one of the greatest political scandals in U.S. History. This event became known as the Teapot Dome Scandal, named for the Teapot Dome rock formation located in Wyoming at one of the government-owned properties involved.

Concern and outrage grew amongst the American public as more corruption and scandal surfaced following the original 1922 story. Citizens became increasingly troubled by how close many of the politicians cited in these scandals were to the White House and presidency. In truth, much of this corruption was directly caused by the questionable company then-president Warren Harding not only kept, but also awarded high-ranking government positions to, following his election in 1921. President Harding rewarded several close politician friends with government positions for their loyalty and assistance with his campaign for presidency. This group of friends turned government officials became known as the “Ohio Gang” and quickly began to run amok in the highest levels of government, accepting bribes, making shady deals, sneaking around with their mistresses, and so much more.

Albert B. Fall was a staunch supporter of Harding, whose friendship and loyalty were rewarded with the position of Secretary of the Interior. As a corporation man who had previously worked as a prospector, miner, mining investor, and land speculator, he was a truly questionable choice for a position responsible for all U.S. Government environmental conservation efforts. Furthermore, his record of decisions in the Senate as one of New Mexico’s two senators was further proof that Fall was not a conservationist. Unfortunately for Fall, his part in the Teapot Dome Scandal would make him the first American cabinet member sent to prison for a crime committed while in office.

One of the two private business owners who bribed Albert Fall was Harry Ford Sinclair, of whom Henry Mason Day was a close friend and loyal employee as Vice President and oil scout of the Sinclair Exploration Company. Day is often described as Sinclair’s “fixer.” Fixers were typically friends of politicians known for trading bribes and favors to essentially “fix things” for others. They used their friendships with government officials and influence created by bribes and/or favors to make things happen for their clients, greasing the right hands and paving the way for those who “hired” them. As Sinclair’s fixer, Henry Mason Day’s tasks included schmoozing VIPs (like the Hardings), often taking them on cruises and other lavish trips. Day was also known to dole out bribes and provide intel on the opposition for Harry F. Sinclair. When traveling with Sinclair and other important officials, he would often destroy the ink blotters following their stay to make sure that nobody could decipher what had been written.

Henry Mason Day, previously known for a few impressive oil deals, skyrocketed into the limelight during the Teapot Dome Scandal investigation that began in April of 1922. The investigation turned up very little evidence of wrong-doing until 1924 when final efforts to follow the bribery money busted the case wide open, leading to several civil and criminal suits that continued late into the 1920s. In 1927, the oil leases were declared corruptly obtained by the Supreme Court. Despite Harry Ford Sinclair and Henry Mason Day’s involvement, they ultimately only served time for jury shadowing the Fall-Sinclair jury in one of the cases related to the Teapot Dome investigation. Both served time in the District of Columbia jail, Sinclair serving six months while Day was sentenced to four months for their contempt of court.

Following his October 1929 release from jail, Henry Mason Day resumed his position as Vice President of the Sinclair Exploration Company. After six years with the company, Day resigned in April of 1930, entering the field of stock exchange by accepting a position with the New York Stock Exchange firm of Redmond & Co. He resigned from Redmond & Co. in 1938 under slightly suspicious circumstances when the firm came under scrutiny for potential infraction of Federal margin regulations.

Henry Mason Day’s familial ties to Smithfield, Virginia and obvious acquaintance with politicians and wealthy New York City socialites likely made him an appealing candidate for the first Board of Directors of St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum. The Day Family had lived in Smithfield for generations and Henry Mason Day was born there in 1886. Furthermore, some of his family still lived in the Smithfield area and it is likely that at least one of Henry Mason Day’s sisters assisted Elizabeth Jordan in contacting him about participating in the 1950s Restoration.

Despite his checkered past, Henry Mason Day served as a thoughtful and dedicated first president of the board. In a July 16, 1956 letter to Elizabeth Jordan, the first Secretary of Historic St. Luke’s Restoration, we get a small glimpse of how Day felt about the restoration where he writes, “This church is not any individual’s church – yours, mine or anyone’s – but is being restored as a national sacred shrine for all Americans, and I intend to continue to give my all to see that the church is restored, as near as it is humanly possible, to the way it is believed to have been originally built.” He spearheaded a successful national campaign which raised the funds to complete an extensive restoration, finished by May of 1957. On the day of the restoration’s unveiling, Henry Mason Day is described as picking the worst spot on the speaker’s roster, speaking only briefly, and finishing his speech with, “This is the happiest day of my life. I’m so happy I can’t say another word.”

A Note from the Author

With this blog, I have attempted to present a decently unbiased retelling of information regarding both Henry Mason Day and the Teapot Dome Scandal. However, I feel it is important to note that St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum and its staff (myself included) will never have a truly unbiased opinion of Henry Mason Day. Under his leadership, the 501©3 organization that we care for deeply was formed in 1953. He, along with Elizabeth Jordan, were two of the biggest driving forces behind the 1950s Restoration of the church building that culminated in its completion and unveiling in May of 1957. Day spearheaded a nationally-recognized fundraising campaign that is still impressive by today’s standards. This was a massive project and undertaking that needed dedicated, passionate people involved for it to be a success and I truly believe Henry Mason Day was one of these much-needed participants. While the restoration was a group effort, who can say how differently things might have turned out if Henry Mason Day hadn’t been involved as the first president of Historic St. Luke’s Restoration? While learning more about him certainly gives us a fascinating look into the complex person that he clearly was, his interesting past does not change the value of the time and care he invested in the historic church building now known as St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum. We are thankful for the role he played in our corporate history, the investments other members of the Day family made over the years (including Henry Mason Day’s brother, Lee Garnett Day, who served on the board as Vice President), and the continued efforts of family members and related organizations like the Nancy Sayles Day Foundation.

Above: A photo of Henry Mason Day (far left) in front of the District Jail, preparing to serve his four month sentence for contempt of court. (gettyimages)

Above: Henry Mason Day (left) discusses Historic St. Luke’s Church with William G. Mennen (right), executive Vice President of the Mennen Co., who donated $50,000 to the restoration of the church building circa 1957.

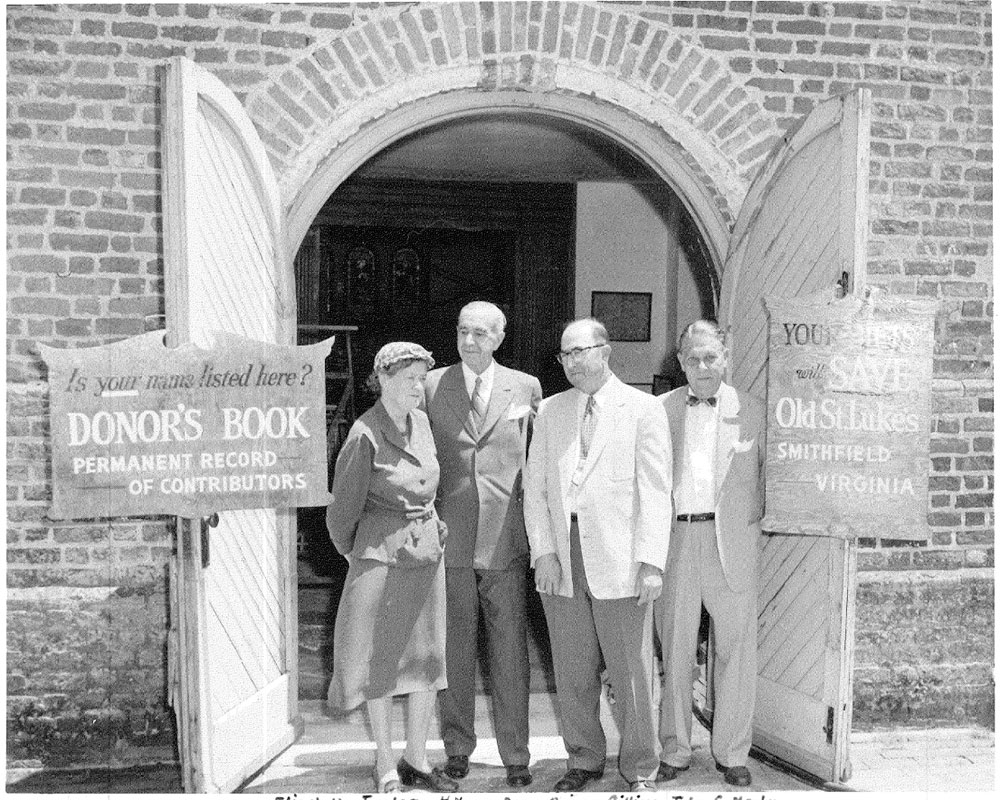

Above: A photo of a few of the first officers of the Board of Directors of St. Luke’s, including Elizabeth Jordan (far left) and Henry Mason Day (second from the left). They are standing in the archway in front of the historic church building.

Above: A photograph of several members of the first St. Luke’s Board of Directors, established in 1953 with the creation of the 501 (c) 3 non-profit organization known as Historic St. Luke’s Restoration. Henry Mason Day stands at the very center of the group.

Above: A portion of a portrait of Henry Mason Day that now hangs in the Conference Room of the Welcome Center at St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum. This oil-on-canvas painting was beautifully restored in 2018 thanks to the generous support of the Nancy Sayles Day Foundation. Nancy Sayles Day, for whom the foundation is named, was married to Lee Garnett Day, one of Henry Mason Day’s brothers. Both Lee Garnett Day and Nancy Sayles Day were instrumental in the 1950s Restoration and Lee even served a term as Vice President of the board of Historic St. Luke’s Restoration. Nancy Sayles Day was an impressive philanthropist who established several foundations and organizations before her death in 1964 at the age of 58.

Enjoy this article? Please consider supporting St. Luke’s with a donation!

Works Referenced

Davis, Barbara J., The Teapot Dome Scandal: Corruption Rocks 1920s America, Compass Point Books, 2007.

McCartney, Laton, The Teapot Dome Scandal: How Big Oil Brought the Harding White House and Tried to Steal the Country, Random House New York, 2008.

The New York Times, “Henry M. Day, 70, Financier, Dead: Former Head of American Foreign Trade Group was Associate of Sinclair,” 14 July 1957, pg. 73.

The New York Times, “Henry Mason Day Quits Sinclair Group; Spent Six Years in Foreign Oil Development,” 30 March 1930, pg. 11.

The Smithfield Times, “Henry Mason Day Died at New York Home July 13th,” 18 July 1957, pg. 1.

Stratton, David H., Tempest over Teapot Dome: The Story of Albert B. Fall, University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, 1998.

About the Author

Rachel Popp, Former Education Coordinator, worked at St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum in some capacity since Fall 2015 when she began researching the site as a student at Christopher Newport University (CNU). At CNU, Popp studied history and minored in Childhood Studies, graduating with a Bachelor’s in History in May 2016. Rachel Popp became the Education Coordinator at St. Luke’s a few months later. She grew up in the outskirts of Virginia Beach, close to the North Carolina Border. Growing up in Virginia, a state with such a profoundly rich history, encouraged Popp’s interest in history from the time that she was young. Today, Rachel Popp spends her spare time diving deeper into the Virginia Museum Community by partnering with, and participating in, organizations such as Virginia Emerging Museum Professionals (Hampton Roads Ambassador), Peninsula Museums Forum (President), and the Virginia Association of Museums (Member).