The British colonization of North America, not unlike most other colonizations, centered around the prospect of wealth and interest in evangelization. It is no surprise then that many of the conflicts that occurred in the British colonies started out of the friction this caused between the Native Americans and the colonists. King Philip’s War of 1675 and Bacon’s Rebellion of 1676 are no exceptions to this. Starting within a year of each other, both had drastic consequences for the course of the British Colonies and into what would become the United States. These two conflicts are some of the most important in early colonial history, and to better understand their causes and consequences it is instrumental to understand how the British colonist’s religious and economic paradigms shaped their perception and place in North America. These main paradigms are Protestantism and Mercantilism.

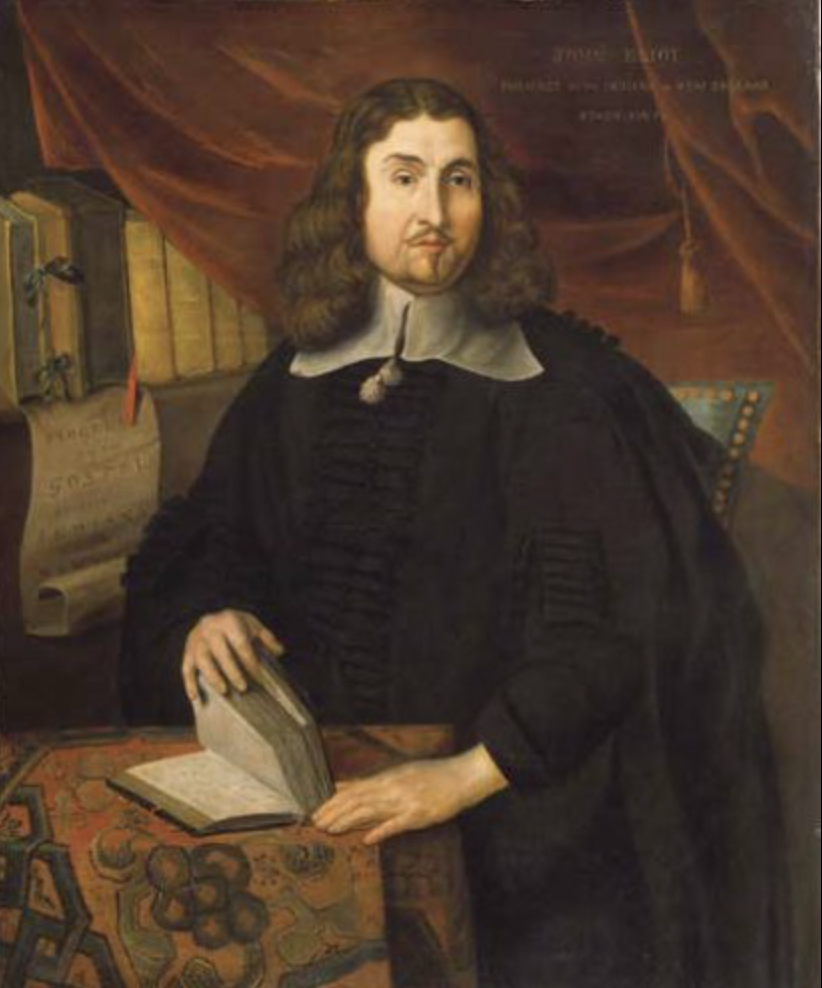

Being that the New England and Virginia colonies were hundreds of miles away from each other, each colony had only approximate knowledge of the various conflicts that took place on each other’s soil. Furthermore, they typically only heard about the most significant battles that occurred. However, as Dr. Wilcomb E. Washburn, professor of History at the College of William & Mary, states, “Despite the lack of official contact, the leaders of each colony followed developments with the other with great interest and no little partiality.” (Washburn, p. 363). He continues to explain that at this point, the Virginians and New Englanders would often hear news about each other through the triangular trade route that went from them to the West Indies. The Virginians who initially heard of the conflict that was brewing between the New Englanders and the Wampanoag tribe and subsequent tribes such as the Nipmuck, Pocumtuck, and Narragansett knew little of the exact details. While the Wampanoag tribe and the northern colonists had enjoyed a largely mutually beneficial relationship of trade, various acts of disrespect and misunderstanding on both sides were straining the relationship. It was further strained by attempts to convert these tribes to Christianity and disputes over land sales. The attempts to create protestant converts were not entirely unsuccessful. In fact, the increased conversion of the Wampanoag tribe caused unrest among the tribe’s religious leaders who likely pressured Philip (Metacom) to reassess his relationship with Protestant preachers such as Reverend John Eliot (Ranlet, 86). Additionally, the colonists who occupied the Northern Colonies in the late 17th century seemed to have little interest in respecting past agreements and treaties made by their parents. The war lasted from June of 1675 to August 1676 and resulted in the death of thousands of Natives (including King Philip himself) and hundreds of colonists. Additionally, the war wiped out the Wampanoag, Narragansett, and many smaller tribes and mostly ended indigenous resistance in southern New England, paving the way for additional English settlements (SCW).

Relations with the Native Americans were worsening across the western front of these eastern colonies and Virginia was no exception. The Governor of Virginia, William Berkely commented on the colony’s own escalating tensions with the Susquehanaug tribe in a letter to the Secretary of the Council of Virginia, Thomas Ludwell, stating, “The infection of the Indians in New-England has dilated it selfe to the Merilanders and the Northern parts of Virginia, and wee have lost about Forty men Women and Children here in potomacke and Rapahannock kild as wee suppose by the Susquehannas home the Marylanders with the Assistance of our men besieged in their for in Maryland.” (Berkely, p. 498). Clearly Berkely considered the conflict with the Susquehanaugs to be, at least in part, a result of the war that was brewing in New England. This gives additional insight into the almost sibling rivalry and scapegoating that had roots in the animosity born out of religious differences between the Anglicans and the Puritans. However, Bacon’s rebellion was largely a result of the poor state of Virginia’s tobacco-based economic and societal structure, which was only made worse by the mercantilistic legislation from Britain. The practice of mercantilism, an economic system centered around imperialism designed to decrease a country’s imports while increasing its exports, put an immense amount of pressure on colonists to either accept what they got from the mother country or fend for themselves and this is typified by the Navigations Acts 1651 and 1660.¹ As William Billings states, “The effects of the Navigation Acts seem mainly to have exacerbated and hastened an already deteriorating situation. In a larger context, the decline of Virginia’s economy after 1660 created widespread disaffection which led a sizable segment of people, both in and out of power, to question certain aspects of the existing political arrangements at all levels.” (Billings, p. 423). Bacon’s Rebellion came to a close by the end of 1676 with the death of Nathan Bacon, the leader of the Rebels, in October. Berkely quickly reestablished control over Jamestown but was removed from his position shortly thereafter. The legislation that followed this conflict was a series of laws pertaining to the status quo and redefining slavery, the particulars of which are a topic for another blog. However, this legislation further entrenched the practice of slavery in the colonies, and with the Navigation Acts adding fuel to the imperial fire, there was no way the colonists would not have continued west.

King Philip’s War and Bacon’s Rebellion are some of the best conflicts to analyze the effects of the mercantilist and 17th-century protestant paradigms in North America. Through analysis, it can be seen that the moral obligation these early 17th-century protestant ministers, such as John Eliot, had to convert the native population and the pressures a mercantilist system put on an already undiversified, declining, and morally dubious economic system guaranteed further conflicts and continued westward expansion from the beginning of the colonial endeavor. While it is hard to cover topics such as these in a short blog such as this, we encourage you to look further into these topics yourself. These sources cited below give incredible information and incite to these important topics that continue to affect us today.

¹It should be noted that many colonists resorted to illegal trading and smuggling with foreign countries such as St. Luke’s patron, Joseph Bridger.

References and Citations:

Berkeley, William. The Papers Of Sir William Berkeley 1605-1677. 1st ed., The Library Of Virginia, 2007, p. 498.

Billings, Warren M. “The Causes Of Bacon’s Rebellion: Some Suggestions”. The Virginia Magazine Of History And Biography, vol 78, no. 4, 1970. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4247595. Accessed 4 May 2022.

Ranlet, Philip. “Another Look At The Causes Of King Philip’s War”. The New England Quarterly, vol 61, no. 1, 1988, p. 79. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/365221. Accessed 4 May 2022.

“Society Of Colonial Wars In The State Of Connecticut – 1675 King Philip’s War”. Colonialwarsct.Org, 2022, https://www.colonialwarsct.org/1675.htm.

Washburn, Wilcomb E. “Governor Berkeley And King Philip’s War”. The New England Quarterly, vol 30, no. 3, 1957, p. 363. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/362992.

Above: A portrait of Metacom (King Philip), the Sachem of the Wampanoag tribe, and the namesake of King Philip’s War.

Above: A portrait of John Eliot, the Puritan minister who was responsible for many Native American conversions to Christianity in the mid-17th-century.

Above: A portrait of Nathaniel Bacon, the man who led the 1676 rebellion against Governor Berkeley known as Bacon’s Rebellion.

Enjoy this article? Please consider supporting St. Luke’s with a donation!

About the Author

Thomas Fosdick has worked at St. Luke’s Historic Church and Museum as a Museum Interpreter since August of 2021. In May of the same year, he graduated from Christopher Newport University with a Degree in American Studies and Political Science while minoring in Leadership Studies. He has been a volunteer and intern with the Mariners’ Museum and Park’s Library Department since January of 2021 and is a member of the Archaeological Society of Virginia. He plans to pursue a Master’s Degree in Maritime Studies starting in August of 2022. Outside of his vocations, he enjoys playing music with his band “Native Love” and spending time with friends and family in and outside of his hometown of Newport News.