The Misconception of Memory: Part One

Written by Research Assistant Lauren Harlow

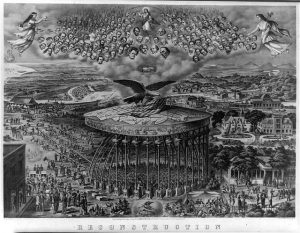

John Lawrence Giles, Reconstruction, 1867

What is history? What is memory? Are these two words synonymous, or do they hold their own meanings? Very plainly, history is the use of collected facts and primary sources in effort to create a living conversation between the past and present. Memory on the other hand, is how a single person or a group of people chooses to remember these historical facts in relation to their personal lives and cultures. While history and memory have impacts on one another, they should be considered separate as they are communicating two different ideas.

Historical memory morphs and evolves with social change, cultural struggle, and monumental events that a society experiences over time. We then collectively remember the aspects of history that most suit our current societal needs, whether that be reconciliation, justice, or identity. Mark Twain put it bluntly as he said, “How history becomes defiled, through lapse of time and the help of the bad memories of men.” Memories are of course invaluable, but far too often they are used to shift the narrative and shape our national identity.

Photo taken at the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, where union and confederate veterans shake hands in a symbolic act of reconciliation.

For example, in the late nineteenth century, America was experiencing a true identity crisis as the Civil War had left citizens with competing memories. The North and South were attempting to reconcile by means of “Blue-Gray Reunions,” which were essentially very public ceremonies where the union and confederate soldiers were shown mingling amongst one another, smiling and waving to the camera — convincing the world that they were friends again. Additionally, both the North and South erected monuments, chapels, graveyards, and statues in an effort to remember the dead and honor those involved. However, not all people were keen on reconciliation. Most African Americans did not warmly join in on forgetting what had happened during and prior to the Civil War. Frederick Douglass famously said, “Well the nation may forget, it may shut its eyes to the past, and frown upon any who may do otherwise, but colored people of this country are bound to keep the past in lively memory till justice shall be done to them.” And thus, from then on, three groups of people chose to remember history differently, and no amount of historical evidence will ever change how these groups feel about these firmly established memories.

Memory is short-lived, and to rely on it for historical truth is unsound. The former president of Colonial Williamsburg, Kenneth Chorley, very poignantly stated, “Do they live in history? Some so live-but wander aimlessly through it’s pages…exiles in a land of fleeting memory.” This will be the first blog in a series that will explore the topic of memory and its influence on American Tradition. Stay tuned for the next blog, where I will further explore America’s obsession with nostalgia and memory.

I am also curious to know your thoughts on history vs. memory. Do you think our memories are invaluable to history? Or perhaps misleading and hurtful at times? Please let me know in the comments below.

Works Referenced:

Huntington, Samuel P. Who are we?: The challenges to America’s national identity. Simon and Schuster, 2004, https://books.google.com/books?id=6xiYiybkE8kC&lpg=PR15&ots=6bvsEAmr7d&dq=Who%20are%20We%3F%3A%20The%20Challenges%20to%20America’s%20National%20Identity&lr&pg=PR15#v=onepage&q=Who%20are%20We?:%20The%20Challenges%20to%20America’s%20National%20Identity&f=false

John Lawrence Giles, “Reconstruction.” New York: Printed by Francis Ratellier, 1867. Library of Congress. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004665356/ (December 15, 2017)

Lipsitz, George. Time passages: Collective memory and American popular culture. U of of Minnesota Press, 1990. https://books.google.com/books?id=dAIDvUmJ5X4C&lpg=PR7&ots=WsX6NUdzAA&dq=Time%20Passages%3A%20Collective%20Memory%20and%20American%20Popular%20Culture&lr&pg=PR7#v=onepage&q=Time%20Passages:%20Collective%20Memory%20and%20American%20Popular%20Culture&f=false

Michael Kammen, Mystic Chords of Memory. New York: Vantage Books, 1993.