In our third and final installment of the series on religion in England and its protectorates during the Commonwealth from 1649 to 1660, we discuss how the Virginia Colony was affected by its home country’s governmental transition to Puritanism.

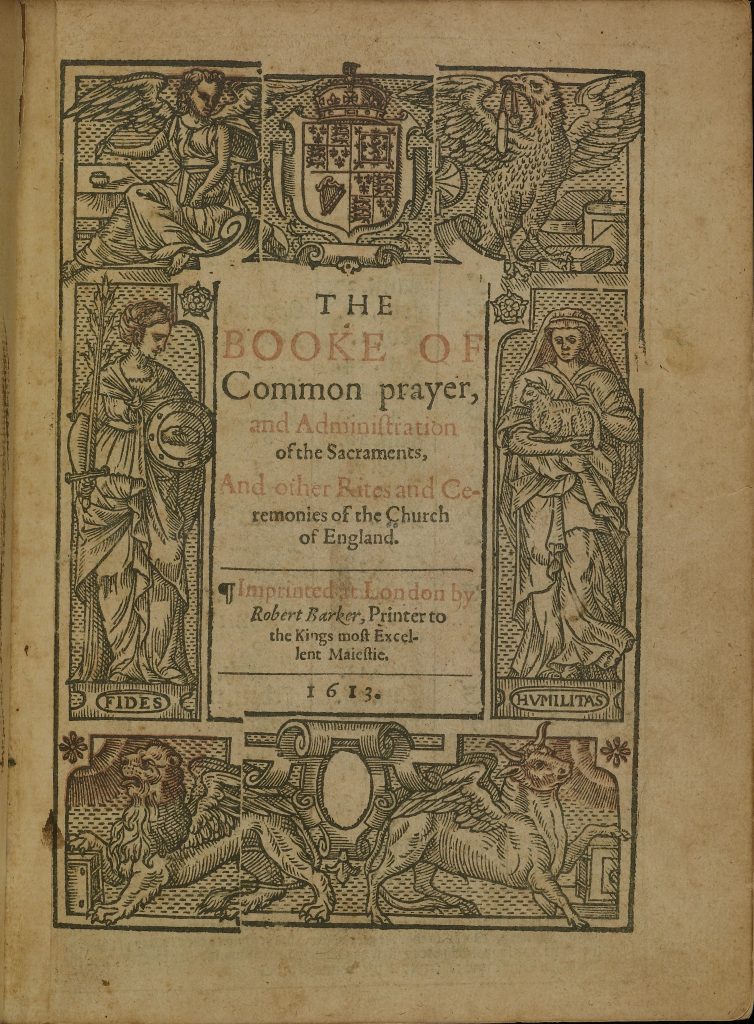

The traditional religious narrative has stated that the Virginia Colony was religious homogenous, consisting of mostly Anglicans. However, archaeological evidence suggests that early Jamestown was as religiously divided as the rest of the burgeoning British Empire and of Europe. Various Puritan-leaning groups were present in the early 17th Century in Virginia and sought to reform the Church of England from within. The need for stakeholders in the Virginia Company meant that religious conformity was a luxury that the investors could not afford. By the 1620s, Puritans began to settle in groups south of the James River including Warrosquoyake Shire. Puritan Edward Bennett was given sizable land grants and undertook to settle some 200 newcomers to the Colony.¹ Christopher Lawne, a leader in the Brownist movement in England also settled in Warrosquoyake, but the fortunes of Virginia Puritans changed dramatically in 1642 with the arrival of a new Governor, Sir William Berkeley. Berkeley, a staunch Cavalier, was given instructions to put down any and all non-conformity within the Colony.² Three clergymen, that had been dispatched from Massachusetts, were expelled by Governor Berkeley upon his arrival because of their views and many of their followers left with them. Puritans believed that the Opechancanough offensive of 1644 was a direct result of Virginia’s apostasy, but Berkeley was unmoved and laws, including mandatory use of the Book of Common Prayer, were passed to suppress any dissenting voices. By the middle of the century, most of the Puritans in Virginia had fled to Maryland and other Colonies. Ironically, when the Puritans were taking control of the government in England, the “Old Dominion” was firmly in control of the Cavaliers. In the early years of the Commonwealth in England, Virginia, still under the control of Berkeley, was doing business with Charles II in exile in the Netherlands. It took until 1652, three years after the execution of Charles I, for Virginia to be brought under the control of the New Model Army and the Commonwealth government. Berkeley was finally driven out and “retired” to his home at Greenspring. Richard Bennett, the nephew of Edward and a new convert to Quakerism, became the Governor. However, life for most Virginians changed very little. Other than a movement to separate themselves from the rest of the Colony on the Eastern Shore, the Virginia government was able to navigate with very little imposition from the authorities in England. Cromwell was engaged in subduing Ireland and Scotland and dealing with religious dissent at home and could devote little to no attention to the North American Colonies.

The most important issue, which was resolved with remarkable speed and efficiency, was the continuation of the House of Burgesses. This gave Virginia a semi-autonomous power to govern itself, so long as the laws passed were not in violation of Parliament. The laws of conformity that Berkeley had put into place were quickly rescinded, but parishes had a nearly free hand to conduct their business as they saw fit.

The Vestries were largely controlled by those who had been adherents to the Monarchy. The English Civil Wars had created an influx of Cavalier refugees right as the Commonwealth was taking shape. Colonel Joseph Bridger was one such emigree to Virginia. Bridger, a son of a churchman, was a military figure who became the head of the Isle of Wight Militia upon his arrival, believed to have been in 1653/4. Bridger would later become the benefactor of the “Old Brick Church” completed near the time of his death in 1686. Bridger was one of many whose ranks swelled the population of Virginia during the Interregnum and helped to shape the direction of the Colony, even while operating in a kind of shadow government at Greenspring. Richard Bennett was in power only until 1655 and much of his time in office was spent navigating through territorial disputes with Maryland, Col. Bridger also aided in this enterprise which shows a degree of cooperation amongst erstwhile political and religious rivals.

Bridger, and many similar leaders from his era, controlled the Vestries with little interference from the government at Jamestown. The settlement after Berkeley’s surrender in 1652 allowed the House of Burgesses to elect their own governors. The succeeding governors, Richard Bennett, Edward Digges, and Lt. Col. Samuel Matthews, had no grand vision for reform of the Virginia churches. In fact, while the last governor during the Commonwealth period, Matthews, was an ally to Oliver Cromwell, he had no discernable Puritan leanings. Months before the restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, the House of Burgesses re-elected Sir. William Berkeley and the Puritan influence within Virginia was officially at an end.

The period of the Commonwealth (1649-1660) was one of great promise for religious toleration, but in execution was mired by the same tensions as those faced by Charles I. Political realities still held sway over very deeply held religious beliefs. It is remarkable that for all of the military achievements of Oliver Cromwell and the New Model Army, the Commonwealth lasted only for a decade. However, the challenge to continually govern a religiously diverse empire would be an ongoing concern well into the 18th Century.

References:

- Kevin Butterfield. “Puritans and Religious Strife in the Early Chesapeake.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 109, no. 1 (2001): 5–36. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4249889.

- Kevin Butterfield. “Puritans and Religious Strife in the Early Chesapeake.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 109, no. 1 (2001): 5–36. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4249889.

Other Sources:

John Frederick Dorman. “Governor Samuel Mathews, Jr.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 74, no. 4 (1966): 429–32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4247248.

Berkeley, William. “Speech of Sir Wm. Berkeley, and Declaration of the Assembly, March, 1651.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 1, no. 1 (1893): 75–81. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4241735.

Tarter, Brent. “Reflections on the Church of England in Colonial Virginia.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 112, no. 4 (2004): 338–71. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4250211.

Above: A portrait of Oliver Cromwell; Lord Protector of the Realm from 1653-1658

Photo credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

Above: A photograph of the 1613 edition of The Book of Common Prayer.

Above: A portrait depicting the Governor of Virginia, Sir William Berkeley, surrendering to the Commonwealth Commissioners.

Above: A photograph of the Ledger Stone for Col. Joseph Bridger in the chancel of St. Luke’s Historic Church and Museum.

Enjoy this article? Please consider supporting St. Luke’s with a donation!

About the Author

John Ericson is the Education Coordinator and a Public Historian for St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum. John holds a degree in History from Roanoke College and a Masters of Divinity from the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg. In addition to John’s role at St. Luke’s, he is the Pastor of Reformation Lutheran Church in Newport News, Virginia. John is married to Oneita Jamerson Ericson, a native of Isle of Wight County, Virginia. They have three sons, Matthew, Thomas, and James, as well as two granddaughters, Carys and Lennon. The Ericsons currently resides in Hampton, Virginia. John has been teaching Reformation History and the Early American Religious Experience for more than thirty years.