Enjoy this article? Please consider supporting St. Luke’s with a donation!

In a conversation with one of my professors, while I was in graduate school, she made the statement: “Race is religion.” At this point in my academic career, I was becoming a scholar of race studying the relationship between religion and Hip Hop so when I heard this statement, it brought my research interests together at the same time. However, that was over four years ago and a lot has changed since that conversation. I completed the program and obtained my Ph.D., but the phrase, “race is religion,” continued to cross my mind every time the topic of race pre-18th century came up as I worked in the field of religion and Hip Hop studies while publishing a special issue and a book. I quite often thought about the phrase “White man’s religion” that has been so popular in Hip Hop and with Black people when talking about Christianity. Most recently, I started to work on a project about religion in early North America and after having several conversations with other scholars on this topic, I finally got it. It clicked. The biggest takeaway from the statement “race is religion” is that the same way we understand racial discrimination today is how should understand religious discrimination pre- 18th century. Let me explain this more in detail and why this is so important to religion in early America.

Whether in college classrooms, or in the news, books, or articles, we talk about race incorrectly. We take how we currently think about race and place it into the minds of people who thought about it very differently than how we currently think about it. Due to the nature of what race is, it is very difficult for scholars to pinpoint its origin but I contend that the turning point in which people began to think about race in the way we do now is the mid-18th century. Therefore, using the term “race” before then does not accurately reflect what was actually being discriminated against before the mid-18th century. The overwhelming guiding force that governed European lives was religion. Since it governed European lives, it drastically affected every people group they came into contact with. If we put religion back into its rightful place, then we can properly understand the importance of religion in shaping early “America” (I put America in quotation marks because the land belonged to the Indigenous peoples for thousands of years before European arrival and did not become America until the 18th century).

What is race? Simply, race is a worldview that orders human differences. A worldview is how a group of people see the world and entails values, assumptions, and beliefs. These beliefs assign characteristics to people and then rank the groups in positions of superiority and inferiority. While this may sound like a generalizable way of grouping people, race has a very specific history that we can follow. It started with European scientists ordering species in the 18th century. In 1749, French scientist Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon introduced the term race into the scientific classification of humankind at the same time European expansion and colonization continued to grow. It is important to note that Europeans had enslaved and colonized Indigenous peoples and Africans for several hundred years by this point. Two more thinkers significantly contributed to how we think about race today, Johann Blumenbach and Thomas Jefferson. Blumenbach was a German scientist who in 1779 divided humans into five “varieties” or races: Caucasian, Mongolian, Ethiopian, American, and Malay. This is where the term Caucasian comes from, showing the modern influence of his categorization still has. Around this same period of time, Jefferson’s thoughts on the Indigenous peoples and Africans were very influential. This is partially because he was sharing his thoughts during a time when the system of slavery had completely solidified in America placing Africans in an inferior status. Jefferson wrote that “the blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time and circumstances, are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind.” Here we get a glimpse at how Jefferson believed the perceived inferiority of Africans could be determined by science and being that he was such an influential figure, his reasoning guided the slaveholders of his day.

Based on this clearly defined understanding of race, we can now address some misconceptions that often lead to its early miscategorization. First, race is not simply skin color. This is probably the biggest misconception and why so many inaccurately point to the existence of race for thousands of years. As explained, there’s a difference between grouping people by skin color and a full system of beliefs that includes defining characteristics such as country of origin, mental capacity, and the history of enslavement and colonization. There is also a difference between race and ethnicity. Ethnicity is more related to shared cultural values and not the scientifically inspired categorization of human differences. Ethnicity is constantly changing and does not necessitate biophysical similarities. A clear example of this is that the term Hispanic is federally recognized as an ethnicity while Hispanics can be racially Black or White.

In the book, Race in North America (2012), Audrey Smedley and Brian Smedley explain that during European colonization, the main force promoting oppression was not racism, but rather ethnocentrism while also providing the etymology of the term race which shows that the term was often used to describe animals. Since Europeans were actually using the word race to define animals, why do so many people claim the existence of race in colonial America? The historically accurate way to understand life in colonial America is to look at religion. Religion was the overarching and guiding force that shaped almost every area of life in colonial America.

One leading indicator of how much we collectively do not account for religion is how absent the Protest Reformation is from many historical accounts of European and American history. The Protestant Reformation literally transformed how we think about God over the past five hundred years. Nearly every mainstream denomination today traces its roots back to this world-changing event. It was the rise of Protestantism and the break from the Catholic church that influenced the British and the Church of England.

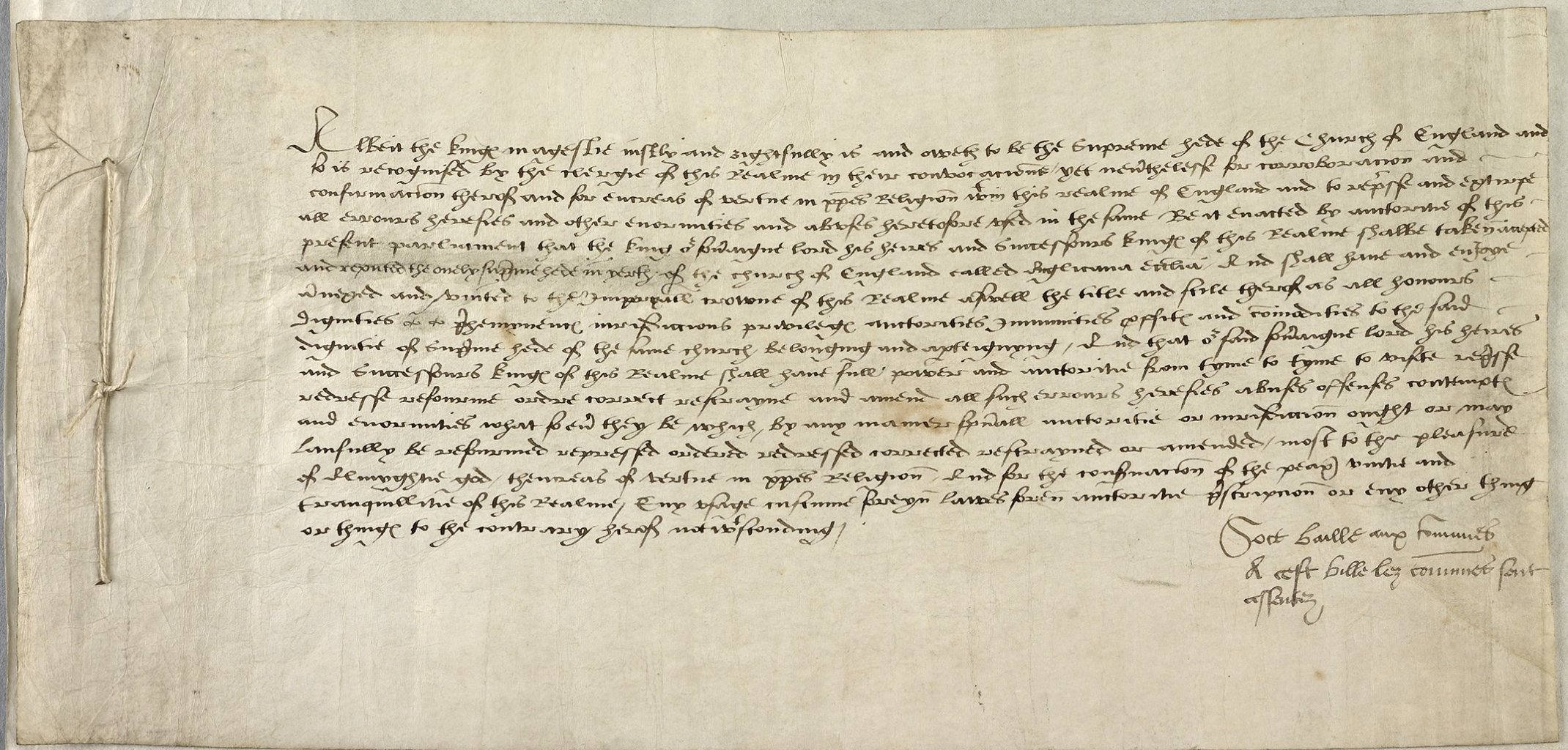

While today we are familiar with White Supremacy, I contend that we must first look at religion’s influence. In the British, Acts of Supremacy, 1534, Henry was identified as the “Supreme Head” of the Church of England, thereby developing a “royal supremacy.” This is an extremely important point for two reasons. First, during this time of Henry VIII’s rule, they were breaking away from the Roman Catholic Church. This was the first instance of a pure Anglo-Saxon, not race, but religion. Second, part of England’s justification for breaking away was a belief in the superiority of a pure pre-Norman church. As a result, it took the ecclesiastical power away from the Pope and gave it to the king, Henry VIII. Therefore, we can directly link the purity of race guided by a belief in White Supremacy back to the purity of religion guided by a belief in a pure Anglo-Saxon religion, i.e. the Church of England!

Scholars overwhelmingly agree that the English learned their methods of colonization used on the Indigenous peoples and Africans from their attempt to colonize Ireland. It is interesting to note that this article entitled, Britain’s Blueprint for Colonialism: Made in Ireland,

about the British developing their colonization tactics on the Irish makes the very mistake that I am arguing against. The author claims that the Irish Catholics were viewed as racially inferior without discussing the Protest Reformation and how it was unsuccessful in Ireland. This is extremely important because this is the main issue the British took with the Irish: they were not the right Christians, they were Catholics. As Kathryn Lin explains in Heathen: Religion and Race in American History (2022), “Catholic veneration of images and relics, the cult of the saints and of the Virgin Mary, and allegiance to the pope all smacked of idolatrous avoidance of the one true God. The Irish had access to the truth, but the failure of the Protestant Reformation to take firm root in Ireland was proof of their essential heathenism, obstinacy, and guilt.” It was not the Irish’s race that the British had a problem with, it was more that they were barbarous pagans and infidels in the minds of the English.

When the British colonists arrived on Turtle Island (an Indigenous name for North America) in 1607, the second Act of Supremacy, 1559, had been passed by parliament and lessened the title of the monarch from Supreme Head to Elizabeth taking the title of “Supreme Governor”. Although the title changed, religion continued to rule with the church and state heavily intertwined. Colonists brought their view of the Irish and applied it to the Indigenous peoples and Africans while colonizing early America. Their religious views led them to believe that God had given them the land and placed them in a superior position over the heathens. Therefore, one of the biggest, catastrophic, and world-changing events in all of history, the trans-Atlantic slave trade and colonization of America, was motivated by religion. This is what John Smith stated in Narratives of early Virginia, 1606-1625:

“Is that the Country is excellent & pleasant, the clime temperate and health full, the ground fertill and good, the commodities to be expected (if well followed) many, for our people, the worst being already past, these former having indured the heate of the day, whereby those that shall succeede, may at ease labour for their profit, in the most sweete, cool, and temperate shade: the action most honorable, and the end to the high glory of God, to the erecting of true religion among Infidells, to the overthrow of superstition and idolatrie, to the winning of many thousands of wandring sheepe, unto Christs fold, who now, and till now, have strayed in the unknowne paths of Paganisme, Idolatrie, and superstition.”

Religion empowered the British to go to unknown lands, enslave and colonize Africans, destroy Indigenous nations, and develop a new country. They were able to justify their harm to the Indigenous peoples because they saw them as savages. Colonists were able to enslave Africans because they were heathens. The English’s religious views led to ecclesiastical governance in the colonized world. Education in colonial America focused on Christian education, whether it be training ministers in college, educating the English people about proper theology, or teaching those they saw as heathens who the true God was. While there was definitely an economic interest and a desire for wealth and power, even how they viewed that money was through a religious lens. How they lived their daily lives was governed by religion, from the clothes they wore to the church being a public meeting place.

In addition to the role of religion in enslavement; colonization; and ecclesiastical governance, there are two enduring areas that I would like to draw out in closing this blog: education and economics. Craig Wilder explains in Ebony and Ivy (2013) that the “first five colleges in the British American colonies were instruments of Christian expansionism.” The first five colleges were Harvard, College of William and Mary, St. John’s College, Yale, and the University of Pennsylvania. The influence those colleges had on this country is undeniable. Most importantly, the takeaway point is that religion was the foundation of education in this country.

While many people are aware of the importance of capitalism in early America, what I would like to draw attention to is the overlap between religion and capitalism. Max Weber famously pushed the idea of a Protestant work ethic but what has not factored much into the public discourse is the Protestant component of capitalism. I contend that we should elevate the importance of religion in thinking about the development of capitalism and its subsequent growth. In the mind of the colonists, in both New England and Virginia, when they were successful, they saw their success as God’s divine providence and approval. This was in all areas of life, including economic growth. Therefore, their capitalistic endeavors aimed to please God. Since religion was the guiding force, money was also used to pay for ministers. Colonists wanted to grow economically, invest economically in Christian education, and invest economically in the work of ministers. The combination of all these factors shows that religion came first and influenced economics.

When looking at economics, education, enslavement, and the everyday lives of Europeans colonists, it is clear that religion was the guiding force. This understanding of religion in early America lays the groundwork to understanding the rise of Evangelicalism and the ongoing influence of religion in America even after the rise of racism. There are numerous contemporary examples that point to the enduring legacy of religion in early America, from Donald Trump’s election to the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade. These devastating events make clear that religion was the first “act of supremacy” and if we do not recognize the role of religion, we will continue to be shocked by religiously influenced violence.

Above: A portrait of Georges-Louis Leclerc, the French scientist who coined the term race in reference to humans.

Above: A painting of the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. The outcome aided in the continued Protestant ascendancy in Ireland.

Above: A photograph of the Act of Supremacy of 1534. Once passed this made King Henry VIII the head of the Church in England.

About the Author

Travis Harris, Ph.D., is the Director of Black Revolutionary Education for the International Black Freedom Alliance and the Editor in Chief for the Journal of Hip Hop Studies. He is actively involved in the Black liberation movement and does not separate his freedom work from his academic work. His primary goal is for all Black people to get free. He has a plethora of experience in the freedom struggle, from getting Black people out of jail to protesting on the front lines to writing policy in order to make systemic change. His research examines the multiple dimensions of African diasporas with a specific focus on race, religion, and Hip Hop. As an interdisciplinary freedom-fighting scholar, he analyzes the complexities of Black life.