When we think about the 4th of July, many of us think of picnics and fireworks. We may even think of the eloquence of Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence, formally adopted on July 4, 1776. (The signing of the Declaration didn’t occur until August 2, 1776). We rarely think of religion in connection with the observance of Independence Day in the U.S.

The Declaration of Independence sought to “place before mankind the common sense of the subject.”(1) Its author, Thomas Jefferson, similarly sought to write what he considered to be the common beliefs of the people, including the right to think and believe as one’s conscience dictated rather than what was prescribed by the ruling class. His intentions for the Declaration of Independence largely stemmed from his belief system as a Natural Law supporter.

Jefferson was not an orthodox Christian thinker but a Natural Law advocate. The Natural Law Tradition suggests that human rights are granted by “nature and nature’s God.” Thus, violations of these natural laws, including the freedoms of individuals to pursue “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” are grounds for overturning the offending government. This is a religious argument that suggests governments don’t grant us rights, God does!

Jefferson and many others of his era believed one of those natural rights is to not have religion imposed on any individual. This was also a new wave of thinking that came from Enlightenment Philosophers and from religious movements like the First Great Awakening. He and other political thinkers of his time were heavily influenced by the religious wars that ravaged European populations in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. At some point, it became apparent that the government could not and should not control people’s beliefs.

In Colonial times, religion was imposed by the governing bodies. Laws requiring the use of the Book of Common Prayer were enforced in Virginia as well as paying taxes to the church. Clergy were required to obtain government licenses in order to legally preach and mandatory attendance to worship services were prescribed by law. While we tend to think of the American Revolution as being brought about by conflict over taxation and representation, John Adams suggested that the possibility of English Bishops coming to the shores of North America was a leading cause.(2) In a letter to the Rev. Dr. Jedidiah Morse, Adams suggested that the imposition of Bishops on American soil would open up the floodgates of religious repression.

In 1777, Thomas Jefferson would go on to write the “Statutes for religious freedom” for the state of Virginia which would pass in Virginia’s State Assembly a decade after the Declaration of Independence. These two documents were among three things for which Jefferson wished to be remembered, along with his founding of the University of Virginia. The laws that we have today, including Article VI of the Constitution and the First Amendment, are designed to ensure that the laws that are ordained by nature and nature’s God are forever a part of our American inheritance. This Sunday, July 4, 2021, is a good time to remember our history and the laws that still protect each and every citizen. We give thanks for those who have fought and died in her defense and celebrate our freedoms on this day, the two-hundred and forty-fifth anniversary of a great expression of the American mind.

Special thanks to Tony Williams of the Bill of Rights Institute for his exemplary work on this topic. His works have influenced the author in various ways.

(Above) “Declaration of Independence,” commissioned 1817, oil-on-canvas painting by John Trumbull depicting the draft of the Declaration of Independence as it is presented to Congress.

Natural Law: “The paradigmatic natural law view holds that (1) the natural law is given by God; (2) it is naturally authoritative over all human beings; and (3) it is naturally knowable by all human beings.” (The Natural Law Tradition in Ethics, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2002.)

Enlightenment: (noun) a philosophical movement of the 18th century marked by a rejection of traditional social, religious, and political ideas and an emphasis on rationalism. (Merriam-Webster Dictionary)

First Great Awakening: religious revival in the British American colonies mainly between about 1720 and the 1740s. (Britannica)

(Above) A portrait of John Adams, an American statesman and attorney who served as the second President of the United States from 1797 – 1801.

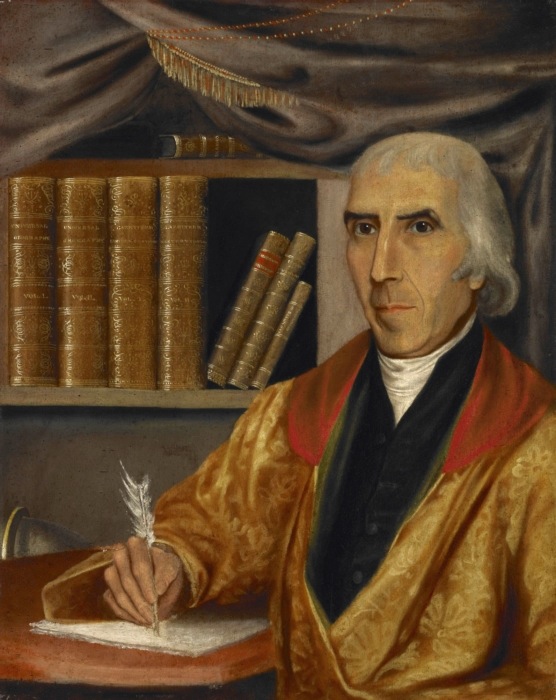

(Above) A portrait of Rev. Dr. Jedidiah Morse, American Congregational minister and geographer known for authoring the first textbook on American geography (1784).

Enjoy this article? Please consider supporting St. Luke’s with a donation!

Works Cited

1) A letter of Thomas Jefferson to Richard Henry Lee dated May 8, 1825.

2) A letter from John Adams to Dr. Jedidiah Morse dated 1815.

About the Author

John Ericson is the Outreach Coordinator and a Public Historian for St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum. John holds a degree in History from Roanoke College and a Masters of Divinity from the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg. In addition to John’s role at St. Luke’s, he is the Pastor of Reformation Lutheran Church in Newport News, Virginia. John is married to Oneita Jamerson Ericson, a native of Isle of Wight County, Virginia. They have three sons, Matthew, Thomas, and James, as well as two granddaughters, Carys and Lennon. The Ericsons currently reside in Hampton, Virginia. John has been teaching Reformation History and the Early American Religious Experience for more than thirty years.