One of the great American narratives is that we were born for purposes of religious freedom. We often turn to the example of the Puritans, who fled persecution in England to establish Plymouth Colony. While the Puritans sought refuge from religious oppression, they themselves would later become persecutors of other religious minorities, such as the Quakers. The Puritans believed that governments were established to enforce God’s laws. Throughout the Colonial period and into our American Republic, violence against religious groups has been an all too frequent occurrence.

One lesser-known event of violence against a religious group occurred in what is now Ohio, within a community known as Gnadenhutten. Gnadenhutten, meaning “huts of grace,” was the established home to a group of Indigenous people from the Mohican and Lenape Tribes who adopted the Moravian faith. The Moravians were some of the earliest groups to protest against what they believed were abuses of the Catholic Church. They can be traced to the Hussites who were Reformers before the 16th century better known Reformation movements. They were known for their missionary zeal and their belief in non-violence. Their pacifist stance put them at odds with both Patriots and the British during the Revolutionary War for their neutrality in the conflict.

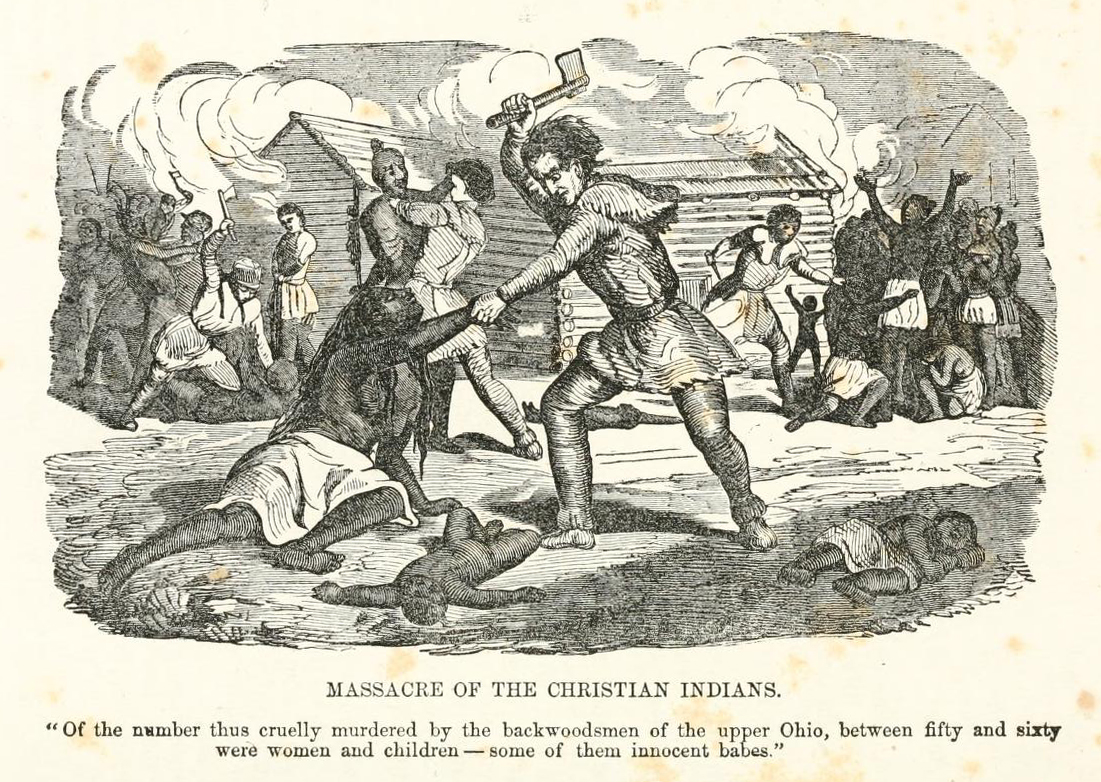

On March 8, 1782, Colonel David Williamson and his Pennsylvania Militiamen descended upon the Moravian settlement, alleging that these peaceful Moravian people were complicit in the murder of American soldiers. Despite their defense, Williamson informed them that they were to be executed. They asked to spend the night in prayer and singing. In the morning Williamson’s troops systematically slaughtered the community, also committing acts of rape against women and young girls before killing them. Eighteen of the militiamen refused to take part in the massacre. On that day, 28 men, 29 women, and 39 children were slaughtered.

Certainly racism against indigenous people played a role in Williamson’s command to murder the Community, but it cannot be understated that pacifist religious movements like that of the Moravians and The Society of Friends (Quakers) have also experienced a long history of oppression and violence against them. On a more positive note, one of the 18 Militiamen who refused to take part in the murder, Obadiah Holmes, Jr managed to save one of the Lenape children and raised the child as his own.

While Williamson and his Militiamen were not punished for their murders, Congress did grant three town sites to the survivors of the Moravaian Community in 1785. Williamson went on to join the Crawford Expedition which sought to retaliate against Indigenous groups that had sided with the British in the closing months of the War. The expedition was a failure and led to the killing of 70 soldiers under William Crawford’s command. Crawford himself was executed as a retaliation for the massacre at Gnadenhutten. President Theodore Roosevelt described the massacre as a “stain on the frontier character that the lapse of time cannot wash away.”(1) Our early American religious experience has been the cause for much celebration in our historical memory but the violence against certain minority religious groups must also remind us of the need to extend our freedoms to all and to be vigilant in our opposition to tyranny and injustice.

(1) Roosevelt, Theodore, The Winning of the West, Volume 2, p. 145. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1889.

Other sources: Kidd, Thomas S. (2019-11-11T22:58:59.000). America’s Religious History: Faith, Politics, and the Shaping of a Nation . Zondervan Academic. Kindle Edition.

Above: 1852 Woodcut of the Gnadenhutten Massacre

Above: Burial site of those killed at Gnadenhutten.

Enjoy this article? Please consider supporting St. Luke’s with a donation!

About the Author

John Ericson is the Education Coordinator and a Public Historian for St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum. John holds a degree in History from Roanoke College and a Masters of Divinity from the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg. In addition to John’s role at St. Luke’s, he is the Pastor of Reformation Lutheran Church in Newport News, Virginia. John is married to Oneita Jamerson Ericson, a native of Isle of Wight County, Virginia. They have three sons, Matthew, Thomas, and James, as well as two granddaughters, Carys and Lennon. The Ericsons currently reside in Hampton, Virginia. John has been teaching Reformation History and the Early American Religious Experience for more than thirty years.