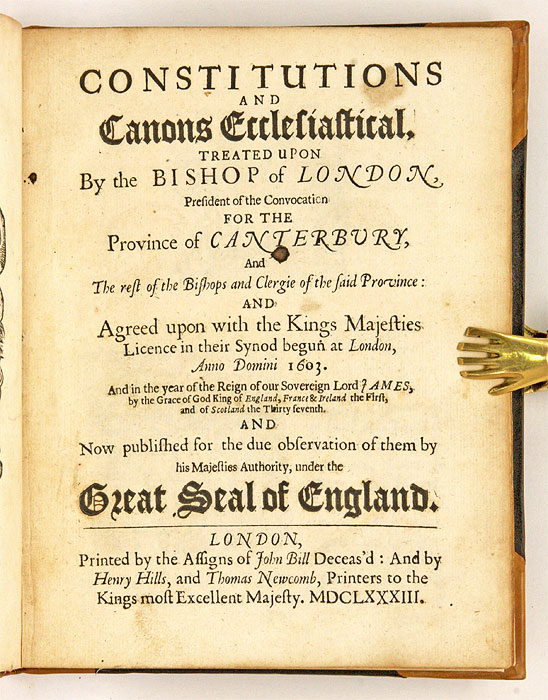

When modern people think of church, we think of a voluntary gathering of like-minded people, who meet to worship God and endeavor to strengthen their spiritual lives. The Church of the 17th century, especially in Virginia, has to be seen in a different light. Within the Empire of Great Britain, the church was a vehicle of the state to promote its imperialistic goals. We may see similar features in the Spanish and Portuguese colonization of the Americas, but, only with the Crown of England do we see religion and government so connected with the monarch being the “governor of the church.” Organizations like the “Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts” were tools for the empire. What we see in Virginia is a church designed primarily to control behavior and keep down rebellions. In the 17th century, there were very few clergymen in the Colony. Anglican polity mandated ordination through the Bishops of the Church of England and no Bishop ever set up shop on the North American continent. The result is that the power of the Virginia church was in the control of the vestries, land wealthy laymen whose goals were not always closely aligned to the “Great Commission.”¹ The labor force, both indentured and enslaved, highly outnumbered this large land-owning ruling class and thus the church became the state’s mechanism to keep the labor force in check and to accomplish the goals of the Empire, extending to the far reaches of the world. In Virginia, vestries were headed by an elaborate system that included the Wardens, Sidesmen, Questmen, Parish Clerks, Vestry Clerks, and other parish officials. Their goal was to keep order, collect the tithe (a parish tax), and prosecute colonists for any moral lapses. The Wardens would function as a kind of prosecuting attorney at yearly gatherings of the courts to punish those who had strayed from the church’s teachings and expectations. These expectations included the requirement that the ministers or other members of the parish proclaim the supremacy of the King in all matters of religion at least four times a year. Violations of the “Constitutions and Canons Ecclesiastical” of 1604 prescribed the death sentence for acts deemed heretical or blasphemous. Sermons in Virginia most often dealt with the expectations of the common people to obey those in authority rather than to proclaim the “good news” of the gospel. The biggest dilemma of this Imperialistic Church was reaching those who lived far from the church buildings. Provisions for “chapels of ease” did not always reach those in the border areas leading clergy to frequently complained about the difficulty in catechizing and caring for the needs of these rural farmers.

Even the individualistic theologies that grew out of the “Great Awakening” did not deter the Church of England from pursuing its Imperialistic goals well into the 18th century. As Katherine Carte notes in her work, Religion and the American Revolution; An Imperial History, “First and most directly, it (the church of the Empire) enmeshed government bodies and religious institutions so that those in government could claim to speak for “protestant” causes and spread their policies through protestant leaders.”

The early American religious experience included laws that gave preference to protestant Christians in holding public office and establishment continued in some states until 1833. Since that time, the courts have been consumed with a myriad of cases that continually seek to define the role of religion in the public arena. However, we can certainly celebrate how an imperialistic church has been transformed into the context we now have: religion functioning independently from the governing institutions and without interference from those holding power.

St. Luke’s Historic Church and Museum has an educational mission to teach the history of our early American religious experience and how that history continues to impact us in the 21st century. Please visit us at https://stlukesmuseum.org/ for more information about our special events, podcast, blogs, and other educational resources.

¹ In Christianity, the Great Commission is the instruction of the resurrected Jesus Christ to his disciples to spread the gospel to all the nations of the world. The Great Commission is outlined in The Gospel According to Matthew 28:16–20.

Sources:

Religion and the American Revolution; An Imperial History Katherine Carté (Published by the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture and the University of North Carolina Press). Omohundro Institute and University of North Carolina Press. Kindle Edition.

Constitutions and Canons Ecclesiastical; https://www.anglican.net/doctrines/1604-canon-law/

Middleton, Arthur Pierce. “The Colonial Virginia Parish.” Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church, vol. 40, no. 4, Historical Society of the Episcopal Church, 1971, pp. 431–46, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42973322.

Above: Bruton Parish Church was the Congregation of the Capital of Virginia from 1699 to 1780. The Royal Governor would most often worship at Bruton during this period.

Above: Constitutions and Canons Ecclesiastical. A copy of this document was required to be on display in every Virginia Parish.

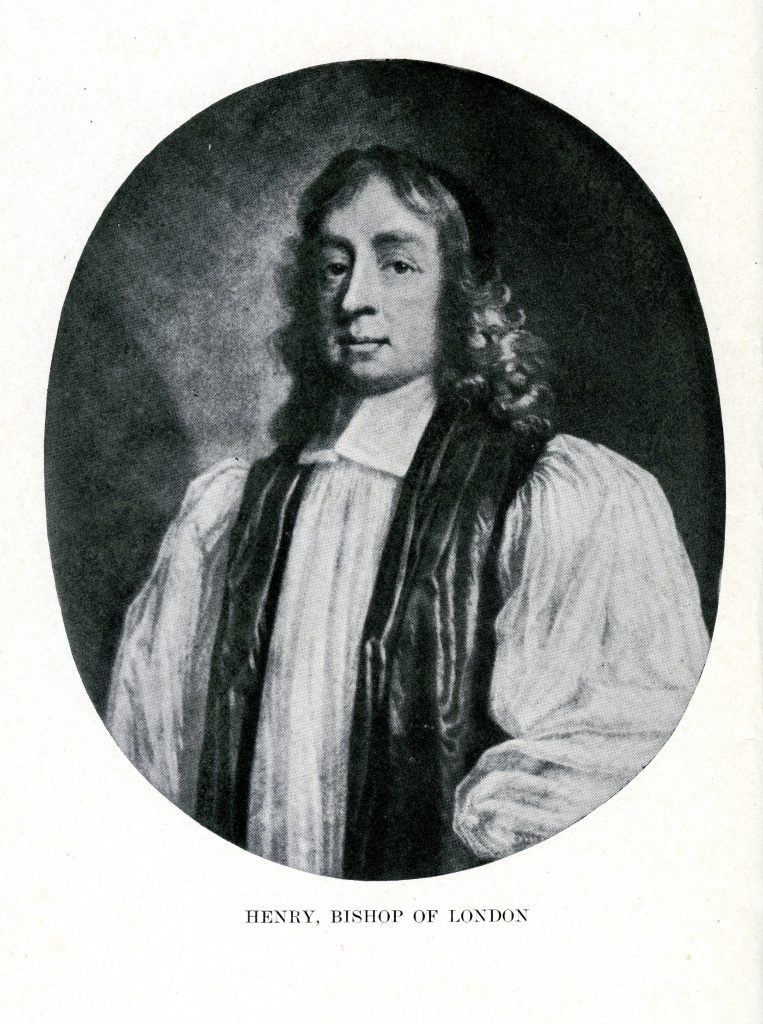

Above: Henry Compton, Bishop of London from 1675 to 1713 oversaw the Colonial Virginia Church from a distance.

Enjoy this article? Please consider supporting St. Luke’s with a donation!

About the Author

John Ericson is the Outreach Coordinator and a Public Historian for St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum. John holds a degree in History from Roanoke College and a Masters of Divinity from the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg. In addition to John’s role at St. Luke’s, he is the Pastor of Reformation Lutheran Church in Newport News, Virginia. John is married to Oneita Jamerson Ericson, a native of Isle of Wight County, Virginia. They have three sons, Matthew, Thomas, and James, as well as two granddaughters, Carys and Lennon. The Ericsons currently resides in Hampton, Virginia. John has been teaching Reformation History and the Early American Religious Experience for more than thirty years.