Enjoy this article? Please consider supporting St. Luke’s with a donation!

The first presence of Christianity in what is now known as Virginia was not Anglicanism. Nearly a century before the Jamestown landing, a number of Spanish missions were attempted in Virginia. There is a suggestion among some Historians that the Dominican efforts in what was called San Miguel de Gualdape, may have reached the James River. While there are many theories surrounding Spanish presence in modern-day Virginia, we know for sure that a Spanish settlement known as Ajacán was present along the Chesapeake Bay in 1570-71. A decade before the Settlement, Spanish Jesuits had educated and brought back to Spain a Native young man named Paquiquineo, whom they called Don Luis de Valasco. Don Luis was baptized in Mexico during a year-long stopover there. Many attempts have been made to link him to the Powhatan Chief Opechancanough, though no such evidence exists to corroborate the theory. Don Luis led the Jesuits back to the Tidewater area and the missionaries were killed in 1571.

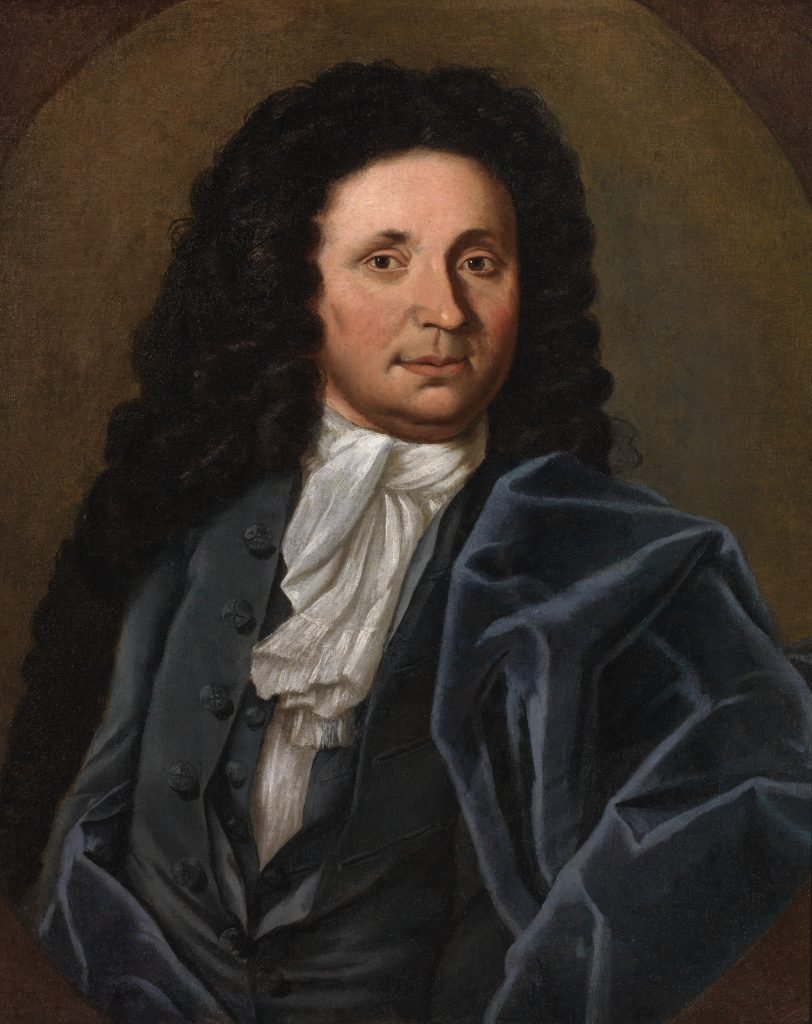

When the English arrived in 1607, the rhetoric of the Anglicans was decidedly anti-Catholic. A sermon was preached by the Rev. William Crenshaw, in the presence of Lord De La Warr (Thomas West) that suggested; “Suffer no Papists; let them not nestle there; nay let the name Pope and Poperie never be heard in Virginia.”¹ Laws were passed that precluded Catholics from holding public office and from starting Catholic parishes. Those who refused to submit to the supremacy of the King were known as recusants. One recusant at Jamestown was Captain Gabriel Archer, a nemesis of Captain John Smith. In 2015 evidence was released that Archer was buried with a reliquary that suggests his likely being a recusant. One exception to the laws requiring office holders to be Anglican was a Mr. George Brent (1640-1700). Brent came to America originally in the Catholic tolerant Colony of Maryland, but, later moved to Stafford County Virginia. Brent held the office of acting Attorney General from 1686 to 1688 and was elected to the House of Burgesses in 1688. These years coincide with the short reign of James II, an openly Roman Catholic monarch who was driven from power in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. After the arrival of William of Orange from the Netherlands, and his English wife Mary, Brent was no longer able to hold office. The anti-Catholic sentiment that followed James II’s reign even removed the protections for Catholics in the Colony of Maryland.

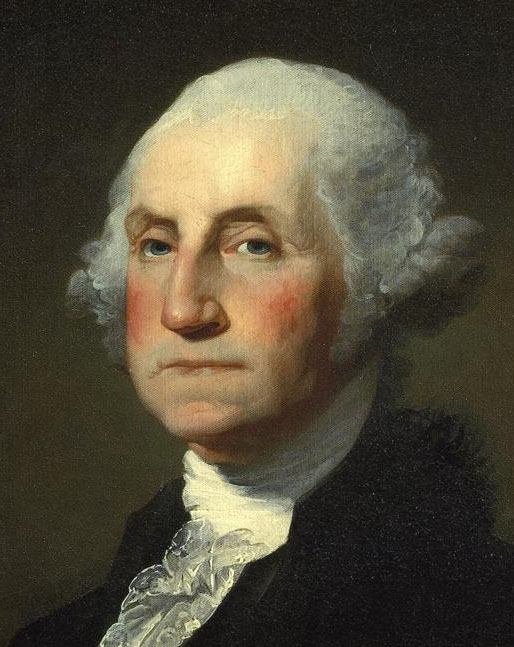

George Washington was required to take an oath, as all officer candidates in the British military were, that he did not support the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation, thereby proving he was not Catholic. In 1775 General Washington was informed of a proposed Guy Fawkes celebration, where customarily it was celebrated with the burning of a depiction of the Pope in effigy. Washington sent an angry announcement that all such plans would be prohibited. Washington later helped Catholics to open the first Catholic Church in Virginia, St. Mary’s in Alexandria. St. Mary’s church building was completed in 1796 and Washington contributed financially to its construction.

St. Luke’s Historic Church and Museum is dedicated to the ideals of religious freedom. As George Washington expressed, in a letter to the Touro Synagogue in Newport Rhode Island in 1790; “happily the Government of the United States gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens, in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.” ²

References:

- GRIFFIN, MARTIN I. J. “CATHOLICS IN COLONIAL VIRGINIA.” Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia 22, no. 2 (1911): 84–100

- http://www.jstor.org/stable/44208153.https://tourosynagogue.org/history/george-washington-letter/

Above: A portrait of George Brent, the only non-Anglican elected to the House of Burgesses.

Above: A photograph of the Touro Synagogue taken in 2017.

Above: A portrait of George Washington. In 1790 he sent a letter to the Touro Synagogue to assure them the Federal government would give, “to bigotry no sanction”.

About the Author

John Ericson is the Education Coordinator and a Public Historian for St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum. John holds a degree in History from Roanoke College and a Masters of Divinity from the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg. In addition to John’s role at St. Luke’s, he is the Pastor of Reformation Lutheran Church in Newport News, Virginia. John is married to Oneita Jamerson Ericson, a native of Isle of Wight County, Virginia. They have three sons, Matthew, Thomas, and James, as well as two granddaughters, Carys and Lennon. The Ericsons currently reside in Hampton, Virginia. John has been teaching Reformation History and the Early American Religious Experience for more than thirty years.