When we talk about the concept of race in the 21st century, we are discussing a socially constructed idea. For the most part, we are talking about skin color when we use the term today. But, at the dawn of the 17th century, race typically identified a group of people with a common ancestor. That group, just as we see in families today, could be quite diverse. It wasn’t until the latter half of the 17th century that we see the development of the concept of race as it is currently viewed.

When English people came to the shores of what is now Virginia, they came with a clearly defined self-identity. They were Christians first, English people second, and sometimes used terms like “free-born” to describe themselves. Their identity did not include any concept of being white. This change came about due to the economic and social conditions of the second half of the 17th century. The first people to harvest the tobacco plants in Virginia were English people whose passage to Virginia was paid for by wealthy landowners as part of indentured servitude. The typical term of service was four to seven years and at the end of that period, the indentured servant would be granted a small plot of land to farm as a free person. The labor was harsh and their treatment by those who oversaw the work was very near to that of slavery. Laws were created that could punish the servant class by adding years to their indenture for any infractions. These laws were often abused by the ruling class, taking advantage of their indentured servants by finding reasons to extend their servitude. By the mid-century, these conditions had created a shortage as less of the labor class came to Virginia.

Indentured servants who managed to complete their terms of service found their living conditions to be less than ideal. They were given land along the borders of the Colony in close proximity to very anxious Native Americans who were concerned about how far west the English might go. By 1676, those disaffected by the ruling class rebelled in what is now known as Bacon’s Rebellion.

Nathaniel Bacon was a highly ambitious and reckless member of the gentry and a cousin to Frances Culpeper Stephens Berkeley, the wife of the Colonial Governor, Sir William Berkeley. His ambition caused him to galvanize the frustrations of those who were on the periphery of Colonial life. In rebellion, hundreds of Bacon’s men marched on Jamestown and burned it to the ground in September 1676. Nathaniel Bacon died the following month on October 26, 1676 of what was then known as the “Bloody Flux” (dysentery). His death caused the rebellion to lose momentum and, though the rebellion continued for a short time without Bacon, ultimately led to defeat. As punishment for the rebellion, 23 rebels were tried and convicted of treason.

The ruling class was concerned that these punishments were not enough to quash the potential for future rebellions. How would the ruling class prevent further collaboration between the English servant class, Indigenous peoples, and West African peoples? This is where our modern concept of race comes into play. If being a member of the elite gentry was simply a matter of wealth and landholdings, theoretically anyone could transform their status. But race, as defined by the color of your skin, was not something you could change. Suddenly, the way English Christian people began to self-identify was that of “white.”

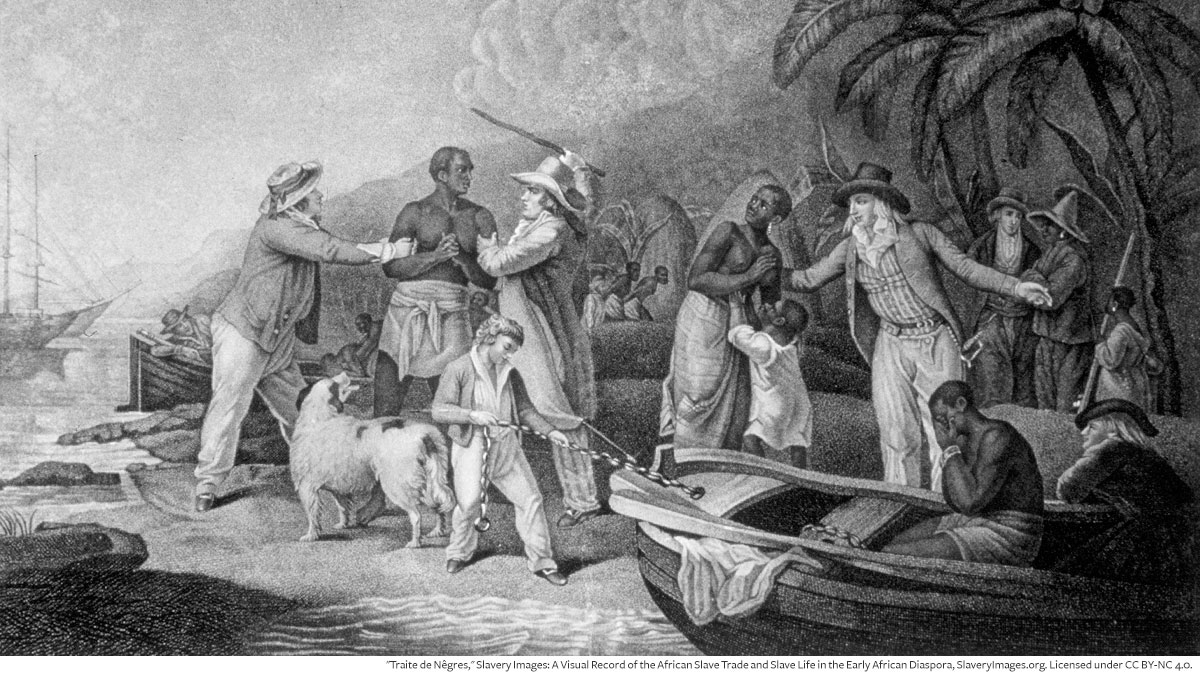

In law, white began to define those holding privilege in both Maryland and Virginia. Longstanding Common Law precedents were overturned in order to justify and maintain this distinction among residents of the Colonies. Soon, those who were not white had their rights taken away. These included the right (and in fact the obligation) to bear arms, the right to assembly, the right to testify in court, and many other rights that now were the sole privileges of the white population. This pacified the English servant class by making them superior to West Africans as the shift towards an entirely enslaved group of laborers from West Africa continued and thrived. In 1650, the population of enslaved people in Virginia was just over 300. By the 1700s, the population had risen to 16,390. These non-white residents, who were at one time free, often found themselves enslaved because of these new laws.

It is important to understand this history as we continue to wrestle with the continuing impact of the concept of race on our society. With this in mind, the Outreach Programs offered by St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum include a lecture entitled; “The Church and the Creation of Race.” Programs may be conducted online. If you would like to set up a program for your church, civic group, or classroom, please contact us at 757-357-3367 or email John Ericson, Outreach Coordinator, at [email protected].

INTERESTING FACTS

Indentured Servant: (noun) a person who signs and is bound by indentures to work for another for a specified time especially in return for payment of travel expenses and maintenance (Merriam-Webster Dictionary).

Above: A portrait of Frances Culpeper Stephens Berkeley, artist unknown, c. 1660.

Above: Portrait of Colonial Governor Sir William Berkeley, oil on canvas by Harriotte L. T. Montague after an original by Sir Peter Lely, Library of Virginia.

Above: Painting of Governor Berkeley challenging Bacon and his men to shoot him. Painting by Sidney King.

Enjoy this article? Please consider supporting St. Luke’s with a donation!

About the Author

John Ericson is the Outreach Coordinator and a Public Historian for St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum. John holds a degree in History from Roanoke College and a Masters of Divinity from the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg. In addition to John’s role at St. Luke’s, he is the Pastor of Reformation Lutheran Church in Newport News, Virginia. John is married to Oneita Jamerson Ericson, a native of Isle of Wight County, Virginia. They have three sons, Matthew, Thomas, and James, as well as two granddaughters, Carys and Lennon. The Ericsons currently reside in Hampton, Virginia. John has been teaching Reformation History and the Early American Religious Experience for more than thirty years.