We (especially those of us working in the Public History Field) often hear the phrase, “History is written by the victors.” This idiom rings particularly true when trying to do any in-depth research of the many Native Indigenous Tribes that dwelled here in North America, before and soon after colonial contact. As we begin the month of November, nationally recognized as Native American Heritage Month, it is important to recognize, respect, and explore this often ignored or sugar-coated part of American history.

In 1607, in what is today known as Isle of Wight County, Virginia, the main village of the Warraskoyack Native People could be found on the Pagan River near where Smithfield, Virginia stands today. Those who take even the most shallow dive into the history of this area will learn that this county was one of eight original shires in Virginia that were formed by order of the King by 1634. It was known as “Warrosquyoake Shire” until its 1637 renaming to “Isle of Wight County.” Furthermore, the river now known as the Pagan River can often be seen on early maps labeled as the Warrosquyoake River or Creek. Many locals often joke that “Warraskoyack” simply had too many spellings, nobody could pronounce it, etc., some of which may have caused its 1637 renaming. Several accepted spellings still remain today including the interesting bastardization of “Warwick Squeak.” Unfortunately, with so little left of this society’s culture, the renaming now stands as further erasure of their history.

The Warraskoyack were an Algonquin-speaking tribe who were part of the Powhatan Paramount Chiefdom when English colonists arrived at Jamestown in 1607. Captain John Smith traded with this tribe as early as Fall 1607 and a decently peaceful relationship continued between the English and the Warraskoyack until 1622. This relationship was initially so successful that the Warraskoyack even warned John Smith and his party in 1609 to be wary of Chief Powhatan when they travelled to meet with him at Werowocomoco (located in modern-day Gloucester, Virginia) in late December of 1609.

The trip took some time, with Smith and his fellow travelers arriving on January 12, 1609. Accounts of this political foray suggest that both parties were ham-handed in their dealings, both trying to establish clear dominance. This unwillingness to compromise, especially on the part of the English colonists who refused to admit their need for Powhatan assistance, created a very rocky relationship with the Powhatan Paramount Chiefdom. This was exacerbated by several clear missteps on the part of the colonists including an incident in 1609 where Smith seized Opechancanough, who was the younger brother of then-Chief Powhatan and was chief of the Pamunkey Tribe at the time, leading him at gunpoint in front of his tribe in what would have been a huge affront to a warrior of such royal status. This affront likely plays a huge role in the conflicts that come to a head in 1622 after Opechancanough becomes Chief Powhatan.

Despite the previously peaceful relationship between the Warraskoyack and the English colonists, conflict between the Powhatan Paramount Chiefdom and the English appears to have destroyed any semblance of this coexistence by 1622. While the 1622 skirmishes certainly ended the last remnants of this relationship, coexistence was rocky before this, conflicts beginning as early as 1610 with the English moving into Warraskoyack land and destroying cornfields. In 1622, an event that is often referred to as the “Powhatan Uprising” began a series of retaliatory skirmishes that led to extreme losses of life on both sides. This had a severe impact on the Warraskoyack whose close proximity to the English colonists made them convenient targets in retaliation towards the Powhatan Paramount Chiefdom. In her book, Pocahontas’s People: The Powhatan Indians of Virginia Through Four Centuries, Helen C. Rountree writes about this where she states:

“The English starved in the next year [1622]; the James River basin Indians may have done likewise. The English were likely to be shot while planting crops, supplies from England were slow in arriving, and only a limited amount of corn was available from fringe groups such as the Patawomecks and new allies such as the Accomacs. However, they managed to muster the men and arms for retaliatory raids on Powhatan groups within reach. The Chickahominies, Nansemonds, Warraskoyacks, and Weyanocks all saw their houses, canoes, and growing corn attacked (and the latter carried away), but the chiefdoms of the York River drainage remained relatively immune because of English weakness.” (1)

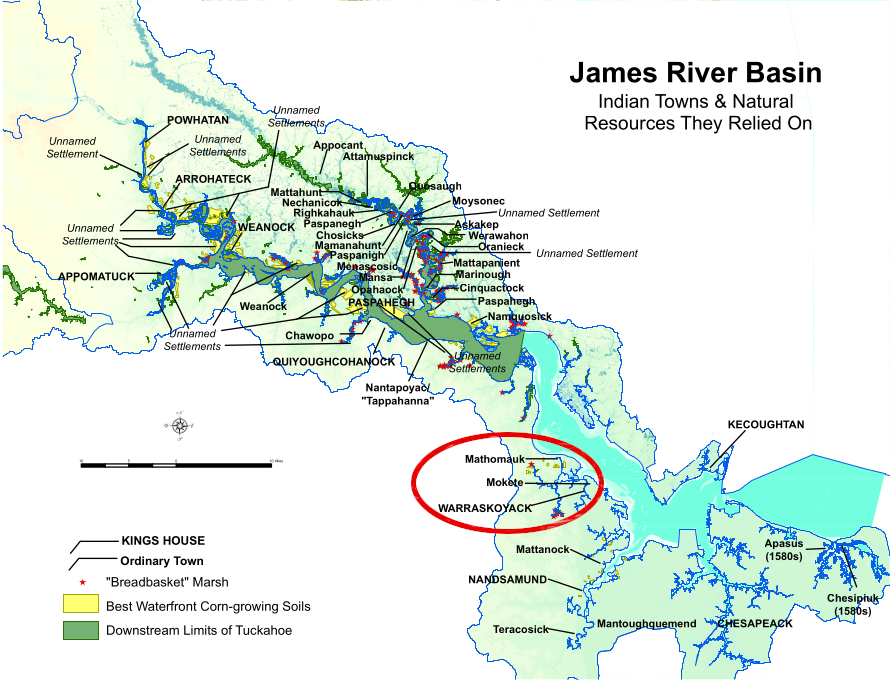

This back-and-forth retaliation continued throughout the 1620s, ultimately forcing the Warraskoyack off of their lands, if not completely wiping them out altogether. Today, there is a group that may have descended from Mathomauk, one of the three Warraskoyack villages, but a 2017 resolution to commend the tribe was not passed by the General Assembly. As we settle into the cooler weather of the season this November and many of us prepare to celebrate Thanksgiving with our families, we ask that you take a moment to recognize and respect the history and struggles of the native inhabitants of the lands we have the privilege of appreciating today.

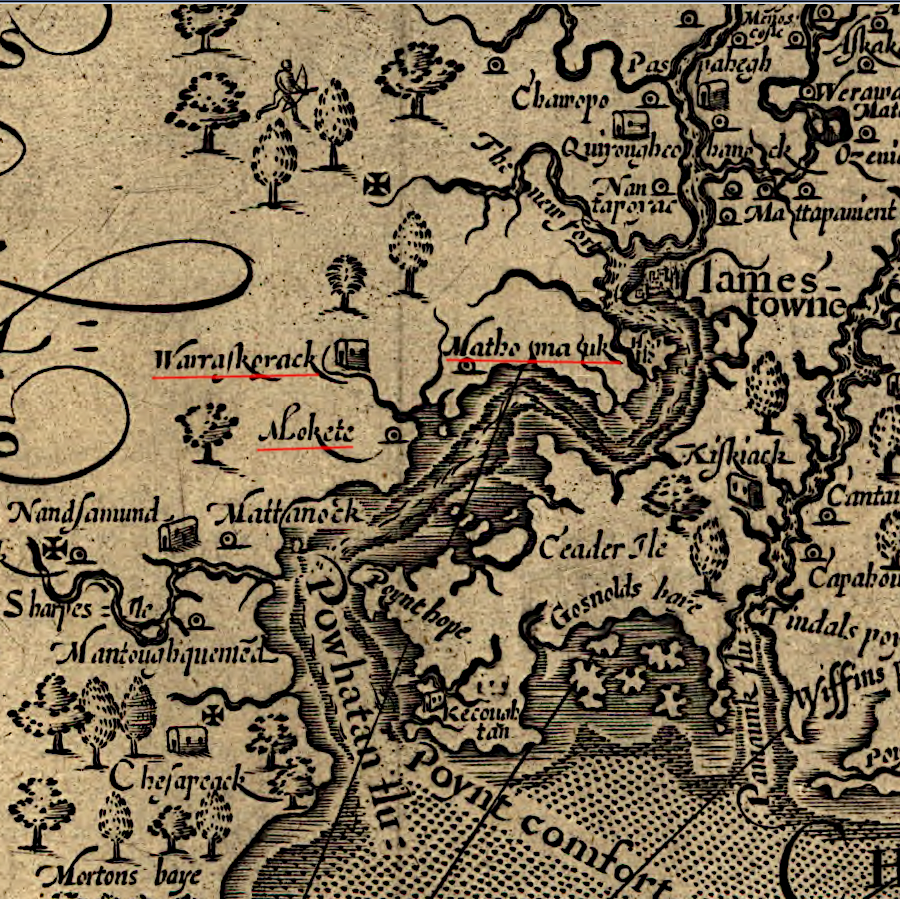

Above: An early map with red lines identifying the three villages of the Warraskoyack Tribe.

Above: A map created by the National Park Service of the James River Basin with a red circle identifying the location of the three Warraskoyack villages.

Enjoy this article? Please consider supporting St. Luke’s with a donation!

Works Cited

(1) Rountree, Helen C., Pocahontas’s People: The Powhatan Indians of Virginia Through Four Centuries, University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, 1990.

Works Referenced

Amin, Reema, Daily Press, “Rushmere community group wants to restore Native American heritage,” 7 May 2016, https://www.dailypress.com/news/isle-of-wight/dp-nws-iw-tylers-beach-redevelopment-20160507-story.html

Encyclopedia of Virginia, Virginia Humanities, “Warraskoyack Indians,” https://encyclopediavirginia.org/geodata/warraskoyack-indians/

Rountree, Helen C., Pocahontas’s People: The Powhatan Indians of Virginia Through Four Centuries, University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, 1990.

“Warraskoyack in Virginia,” http://www.virginiaplaces.org/nativeamerican/warraskoyack.html

About the Author

Rachel Popp, Former Education Coordinator, worked at St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum in some capacity since Fall 2015 when she began researching the site as a student at Christopher Newport University (CNU). At CNU, Popp studied history and minored in Childhood Studies, graduating with a Bachelor’s in History in May 2016. Rachel Popp became the Education Coordinator at St. Luke’s a few months later. She grew up in the outskirts of Virginia Beach, close to the North Carolina Border. Growing up in Virginia, a state with such a profoundly rich history, encouraged Popp’s interest in history from the time that she was young. Today, Rachel Popp spends her spare time diving deeper into the Virginia Museum Community by partnering with, and participating in, organizations such as Virginia Emerging Museum Professionals (Hampton Roads Ambassador), Peninsula Museums Forum (President), and the Virginia Association of Museums (Member).