In a famous letter written in 1790 to the Touro Synagogue in Newport Rhode Island, George Washington suggested; “For happily the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens, in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.” Washington believed that differing religious beliefs should not be the cause of violence, as was the case through so much of European history. Washington was not alone in this sentiment. James Madison, the chief architect of the Constitution, was a staunch advocate of religious freedom. Article VI of the Constitution states that there will be, “no religious tests for holding public office,” and the first amendment prohibits the federal government from having an established religion. The fourteenth amendment extends that prohibition to the states. Religious Freedom is a hallmark of our American Republic. However, these freedoms have been sorely tested over the years, especially in the case of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Joseph Smith, founder of Mormonism and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, was born in 1805 in Sharon, Vermont. At age 14, he described a vision where God informed him that all of the religious traditions were wrong. A few years later, an encounter with an angel revealed golden tablets that would be the source of the Book of Mormon, published by Smith for the first time in 1830. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was formally organized by Joseph Smith on April 6, 1830. It was a movement very different from the experience of most American Christians. Among the tenants of this burgeoning Mormon faith was a commitment to communal living. Non-Mormons were concerned that when a Mormon family moved into their town, many more were to follow. They were concerned that this church, of which they were very suspicious, would be able to vote as a power block. These fears created animosity wherever Mormon Communities went and eventually incited violence.

In Missouri in 1837, this growing animosity towards Mormons escalated into all-out war. On October 27, 1838, Missouri Governor Lilburn Boggs issued an executive order calling Mormons the enemy and encouraging citizens to drive them out and even exterminate them. Many citizens took up the call and a violent mob attacked the Mormon Community at Haun’s Mill where 17 Latter-day Saints followers were massacred. By 1839, Smith and his church migrated to Illinois and began building Temple at Nauvoo in Western Illinois.

Despite violence towards Mormons, the church was growing in large numbers. By 1840, the Latter-day Saints was a large enough religious organization to successfully send 6,000 Missionaries to Great Britain. But the Latter-day Saints were met with continual opposition along the way. In 1844, Joseph Smith declared his intention to run for the U.S. Presidency, to which many reacted violently. After an incident that included the destruction of a printing press that had published anti-Mormon sentiments, Smith and his brother Hyrum were murdered by a mob at the jail in Carthage, Illinois. But the Latter-day Saints continued their mission under the new leadership of Brigham Young.

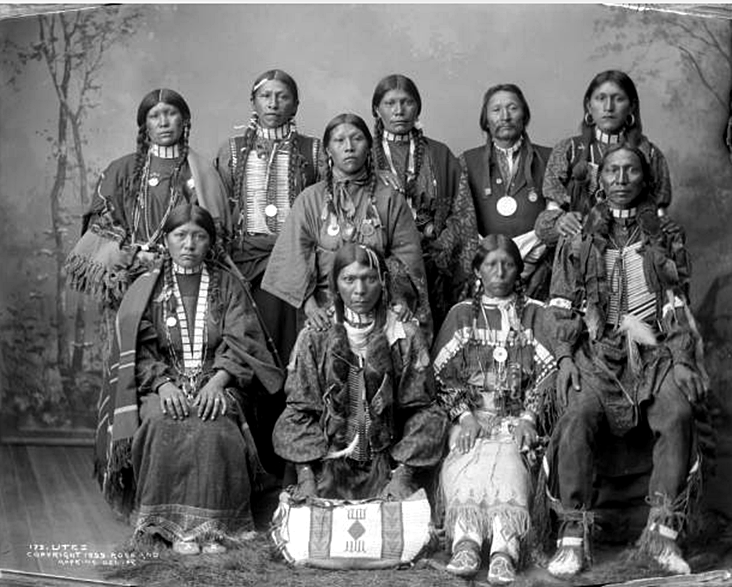

By 1848, the Mormons made their journey outside of the United States in the Utah Territory. In the Great Salt Lake region, the Mormons found their home. The native population of the Ute Tribe also lived in this region and Brigham Young was inclined to work with and cooperate with the Utes at first. He was quoted as saying, “it’s cheaper to feed them than to fight them,” but continued conflicts over access to drinking water and control of the land ultimately led to war. The Black Hawk War raged from 1865-1872 and would permanently displace the Ute Tribe, forcing them onto reservation lands. The U.S. Army intervened against the Ute and other Indigenous Tribes.

The Church of Latter-day Saints would continue to build their home base in the Utah Territory (Utah would become a State in 1896). The violence that was inflicted on them, and which they inflicted on the Utes, is a legacy that teaches us about the importance of religious freedom and living peaceably with people of differing beliefs. Washington’s assertion that our government give, “to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance,” is an ideal that can only survive if “we the people” remember our history and insist on preserving the freedoms we hold so dear.

Above: A portrait of Joseph Smith, founder of Mormonism and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Above: A photo of the Temple at Nauvoo in Western Illinois.

Above: A photo of several members of the Ute Tribe.

Enjoy this article? Please consider supporting St. Luke’s with a donation!

About the Author

John Ericson is the Outreach Coordinator and a Public Historian for St. Luke’s Historic Church & Museum. John holds a degree in History from Roanoke College and a Masters of Divinity from the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg. In addition to John’s role at St. Luke’s, he is the Pastor of Reformation Lutheran Church in Newport News, Virginia. John is married to Oneita Jamerson Ericson, a native of Isle of Wight County, Virginia. They have three sons, Matthew, Thomas, and James, as well as two granddaughters, Carys and Lennon. The Ericsons currently reside in Hampton, Virginia. John has been teaching Reformation History and the Early American Religious Experience for more than thirty years.